Joseph Dietzgen

Joseph Dietzgen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 9, 1828 |

| Died | April 15, 1888 (aged 59) Chicago, United States |

| Era | 19th century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Marxism |

Main interests | Epistemology, logic, dialectics |

Notable ideas | Dialectical materialism |

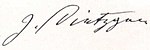

| Signature | |

| |

Peter Josef Dietzgen (December 9, 1828 – April 15, 1888) was a German socialist philosopher, Marxist and journalist.

Dietzgen was born in Blankenberg in the Rhine Province of Prussia. He was the first of five children of father Johann Gottfried Anno Dietzgen (1794–1887) and mother Anna Margaretha Lückerath (1808–1881). He was, like his father, a tanner by profession; inheriting his uncle's business in Siegburg. Entirely self-educated, he developed the notion of dialectical materialism independently from Marx and Engels as an independent philosopher of socialist theory. He had one son, Eugene Dietzgen.

Life

[edit]Early on in his youth, Joseph Dietzgen worked with the famed Forty-Eighters of the 1848 German Revolution. It was there that he first met Karl Marx and other socialist revolutionaries, and began his career as a socialist philosopher. Following the failure of the 1848 Revolution he spent some time in the United States from 1849 to 1851, returning once again for a visit from 1859 to 1861. While in the New World he traversed the American South and witnessed first hand the lynchings which had come to characterize the slave states. During the period between his travels, Dietzgen joined the Alliance of Communists with Karl Marx back in Germany in 1852. In 1853, after marrying his wife Cordula Finke, he established his tannery business in Winterscheid (today part of Ruppichteroth), Germany. When he returned to the United States in 1859 he set up another tannery in Montgomery, Alabama. From 1864 to 1868, he lived with his son Eugene in St. Petersburg, where he was manager of the state tannery. He worked with the Tsar of Russia on improvement of the Russian methods.[1] During his time spent in Russia he wrote one of his earliest texts, The Nature of Human Brain-Work, which was published in 1869. Upon his first reading of the text, Marx forwarded a copy to Engels, remarking, "My opinion is that J. Dietzgen would do better to condense all his ideas into two printer's sheets and have them published under his own name as a tanner. If he publishes them in the size he is proposing, he will discredit himself with his lack of dialectical development and his way of going round in circles."[2][3] While he traveled, his wife managed the family tannery business back in Germany until he returned in mid-1869.[1] Once he was back home, he was visited by Marx and his daughter, who proclaimed that Joseph had become "the Philosopher" of socialism. By 1870, Marx had embraced Dietzgen as a friend, and later praised him and his theory of dialectical materialism in the 2nd edition of the first volume of Das Kapital.

On June 8, 1878, Dietzgen was arrested following the publication of a lecture he gave in Cologne: The future of the social democracy. He spent 3 months in prison on remand before his trial was held. Although Joseph was released along with copies of his article, he was re-arrested twice and finally released.[4] In 1881 Joseph sent his son Eugene to the United States in order to avoid the Kaiser's upcoming army draft, to safeguard his articles and documents, as well as to secure a family home in the new world. Young Eugene was 19 when he arrived in New York, but quickly jump started a thriving family business in Chicago, the Eugene Dietzgen Company. It became one of the world's top drafting and surveying supply manufacturers and distributors and remained such through most of the 20th century. The company still exists today as a division of Nashua Paper, and its two buildings still stand in Chicago's now trendy Printer's Row and Lincoln Park areas.[5][6] During this period, Eugene and Joseph kept in close contact through extensive letters which are currently being documented and published. In the same year, Joseph ran for the elections of the German Reichstag (the parliament), but emigrated in 1884 to New York City. He moved to Chicago two years later, where he became editor at the Arbeiterzeitung. Unfortunately Joseph's death in 1888 marked an end to his son's dependency, but his family line would continue to be part of some of the biggest engagements of the 20th century; from World War I, to the 1936 Berlin Olympics, to the heart of World War II.[7]

Dietzgen's words and life have for some underscored the unity that existed on the political left at the time of the First International, before Anarchists and Marxists were later divided: "For my part, I lay little stress on the distinction, whether a man is an anarchist or a socialist, because it seems to me that too much weight is attributed to this difference." This suggests he took a more concilliatory, or at least more aloof view of the disputes of the moment (see Anarchism and Marxism).

Philosophy

[edit]Dietzgen's most significant influence is generally described as specific philosophical theory of dialectical materialism, drawing from Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's concept of dialectic and materialism, in particular that of Ludwig Feuerbach (himself earlier a Young Hegelian). Similar positions were developed independently by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their writings. According to his preface to Dietzgen's "The Positive Outcome of Philosophy", it seems the Communist Manifesto in particular was significantly influential on the development of his thought prior to his earliest philosophical works.

In the earlier "Thirteenth Letter on Logic", Joseph Dietzgen gave the following summary of his philosophical positions:

"The red thread winding through all these letters deals with the following points: The instrument of thought is a thing like all other common things, a part or attribute of the universe. It belongs particularly to the general category of being and is an apparatus which produces a detailed picture of human experience by categorical classification or distinction. In order to use this apparatus correctly, one must fully grasp the fact that the world unit is multiform and that all multiformity is a unit. It is the solution of the riddle of the ancient Eleatic philosophy: How can the one be contained in the many, and the many in one

An explicit evocation of the Eleatics (Parmenides, Zeno of Elea and Melissus of Samos) in particular is distinctive, and sets the language apart from the "mainstream" of dialectical materialism as is more commonly considered.

After his death, Joseph's son Eugen gave the following view of the relevance of his father's philosophy:

If the founders of historical materialism, and their followers, in a whole series of convincing historical investigations, proved the connection between economic and spiritual development, and the dependence of the latter, in the final analysis, on economic relations, nevertheless they did not prove that this dependence of the spirit is rooted in its nature and in the nature of the universe. Marx and Engels thought that they had ousted the last spectres of idealism from the understanding of history. This was a mistake, for the metaphysical spectres found a niche for themselves in the unexplained essence of the human spirit and in the universal whole which is closely associated with the latter. Only a scientifically verified criticism of cognition could eject idealism from here. (p iv)

This prompted a negative reaction Georgi Plekhanov, as one of the earliest Russian Marxists (as well as co-founder of the Iskra magazine and Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party, and himself the author of "The Monist View of History", an attempt at an interpretation of historical materialism, and "reconstruction" of the views of Karl Marx:

Despite all our respect for the noble memory of the German worker-philosopher, and despite our personal sympathy for his son, we find ourselves compelled to protest resolutely against the main idea of the preface from which we have just quoted. In it, the relationship of Joseph Dietzgen to Marx and Engels is quite wrongly stated"[8]

It is of some notability Vladimir Lenin extensively quoted the writings of Joseph Dietzgen in his later notorious polemic against Ernst Mach (and more pertinently and directly, his rival Alexander Bogdanov), Materialism and Empiriocriticism: Critical Comments on a Reactionary Philosophy (which was later made part of exemplary canon, in particular during the rule of Joseph Stalin). Besides the mentioned text, Lenin also made certain erstwhile notes concerning Dietzgen among the notes later grouped as his Philosophical Notebooks (Collected Works, Vol. 38., Lawrence & Wishart, 1980). [9]

In the note on pages 403-406 he compared him unfavourably to Feuerbach:

...To be does not mean to exist in thought.

In this respect Feuerbach’s philosophy is far clearer than the philosophy of Dietzgen. “The proof that something exists,” Feuerbach remarks, “has no

other meaning than that something exists not in thought alone.”

Death

[edit]Dietzgen died at home smoking a cigar. He had taken a stroll in Lincoln Park, and was having a political discussion in a "vivacious and excited" manner about the "imminent collapse of capitalist production". He stopped in mid-sentence with his hand in the air – dead of paralysis of the heart. He is currently buried at the Waldheim Cemetery[10] (now Forest Home Cemetery), in Forest Park, Chicago, near the graves of those executed after the Haymarket Affair (popularly known as the Haymarket Martyrs).

Legacy

[edit]Anton Pannekoek, the Dutch astronomer and council communist (a left-communist, belong to the group or position which Lenin called "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder[11] noted that, in "Materialism and Empirio-criticism", Lenin cited Dietzgen's penultimately composed work (the "Letters on Logic"), but not the final one to be composed ("The Positive Outcome of Philosophy").

In his 1938 book on Lenin, written after the work had already been given the status of a paradigm of philosophy in the USSR, Pannekoek included a highly critical response to the text. In particular, Pannekoek charged that Lenin had completely ignored Dietzgen's last composed philosophical work and therefore misunderstood the development of Dietzgen's thought.[12]

It is largely through the legacy of the followers and supporters of Pannekoek and his positions (which sought support and legitimacy from Dietzgen, in particular in groups like the Council Communist Collective) that the writings of Dietzgen are most discussed and attract the most interest.

In fact, it seems Pannekoek treated Dietzgen’s writings as a key source for textual legitimacy. Besides that, there has historically remained little interest in Dietzgen beyond the lifetimes of his contemporaries.

Considering the background of Pannekoek's views, it seems his treatment of Dietzgen was in some part as a potential source of, or "license" for critique of, at least some qualities "mainstream" Marxist discourse (that would be able to maintain legitimacy within its discourse).

Though he was sometimes mentioned and of some relevance to the first “Marxist” generation, it is perhaps that much of what had been Pannekoek’s attraction to Dietzgen, was arguably already being superseded in many circles in the eyes many to whom it might have appealed. For example, one attraction may have been a desire for certain more extensive philosophical investigation as well as justification of one’s position within the bounds of, and on the basis of a strictly understood form of Marxist discourse.

In particular, it seems Dietzgen did not any others those who nevertheless intended to apply or make reference to a specifically "Marxist" normative structure of discourse, with some adherence its characteristic nominal rules for justification of positions.

With the downfall of the Second International and other developments creating new and different discursive lines of division, the more pure textual-critical approaches lost their attraction because of greater opposition to or disillusionment with, claims to authority or superseding authority on the basis of textual sources such as those that Pannekoek referenced in his polemics.

Dietzgen figured on a commemorative postage stamp issued in the German Democratic Republic.[13]

Major works

[edit]- Das Wesen der menschlichen Kopfarbeit, 1869, engl "The Nature of Human Brainwork",[1]

- "The Religion of Social Democracy" (in six sermons from 1870 to 1875)[2].

- "Scientific Socialism"[3] (1873).

- "The Ethics of Social Democracy" (1875).[4]

- "Social Democratic Philosophy" (1876).[5]

- "The Inconceivable: a Special Chapter in Social-Democratic Philosophy" (1877).

- "The Limits of Cognition" (1877).[6][7]

- "Our Professors on the Limits of Cognition" (1878)[8].

- "Letters on Logic" (addressed to Eugen Dietzgen) (1880–1884).

- "Excursions of a Socialist into the Domain of Epistemology" (1886).[9]

- "The Positive Outcome of Philosophy" (1887).

More recent editions:

- Nature of Human Brain Work: An Introduction to Dialectics, Left Bank Books, Reprint 1984

- Philosophical Essays on Socialism and Science, Religion, Ethics; Critique-Of-Reason and the World-At-Large, Kessinger Publications, 2004, ISBN 1-4326-1513-0

- The Positive Outcome of Philosophy; The Nature of Human Brain Work; Letters on Logic, Kessinger Publications, 2007, ISBN 0-548-22210-X

Collected writings

[edit]- Josef Dietzgen, Sämtliche Schriften, hrsg. von Eugen Dietzgen, 4. Auflage, Berlin, 1930

- Joseph Dietzgen, Schriften in drei Bänden, hrsg. von der Arbeitsgruppe für Philosophie an der Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR zu Berlin, Berlin, 1961–1965

Secondary literature

[edit]English

- Anton Pannekoek: "The Standpoint and Significance of Josef Dietzgen's Philosophical Works" – Introduction to Joseph Dietzgen, The Positive Outcome of Philosophy, Chicago, 1928

German

- SPD-Protokollnotizen S. 176; Liebknecht 1988, Biographisches Lexikon 1970, Dietzgen 1930, Friedrich Ebert-Stiftung, Digitale Bibliothek

- P. Dr. Gabriel Busch O.S.B.: Im Spiegel der Sieg, Verlag Abtei Michaelsberg, Siegburg 1979

- Josef Dietzgen, Sämtliche Schriften, hrsg. von Eugen Dietzgen, 4. Auflage, Berlin, 1930

- Joseph Dietzgen, Schriften in drei Bänden, hrsg. von der Arbeitsgruppe für Philosophie an der Akademie der Wissenschaften der DDR zu Berlin, Berlin, 1961–1965

- Otto Finger, Joseph Dietzgen – Beitrag zu den Leistungen des deutschen Arbeiterphilosophen, Berlin, 1977

- Gerhard Huck, Joseph Dietzgen (1828–1888) – Ein Beitrag zur Ideengeschichte des Sozialismus im 19. Jahrhundert, in der Reihe Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Bochumer Historische Schriften, Band 22, Stuttgart, 1979, ISBN 3-12-913170-1

- Horst Gräbner, Joseph Dietzgens publizistische Tätigkeit, unveröffentlichte Magisterarbeit an der J-W-G-Universität, Frankfurt/M, 1982

- Anton Pannekoek, "Die Stellung u. Bedeutung von J. Dietzgens philosophischen Arbeiten" in: Josef Dietzgen, Das Wesen der menschlichen Kopfarbeit; Eine abermalige Kritik der reinen und praktischen Vernunft, Stuttgart: J. H. W. Dietz Nachf., 1903

Dutch

- Jasper Schaaf, De dialectisch-materialistische filosofie van Joseph Dietzgen, Kampen, 1993

References

[edit]- ^ a b Feldmann, Vera Dietzgen, interview by Joshua J. Morris. Joseph Dietzgen Research (April 16, 2008)

- ^ Letter to Engels of October 4, 1868.

- ^ "Marx-Engels Collected Works, Volume 43" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ^ Joseph Dietzgen - a sketch of his life by Eugene Dietzgen

- ^ Eugene Dietzgen

- ^ "Eugene Dietzgen Company Historÿ". Dietzgen (division of Nashua Paper). Archived from the original on October 26, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ^ Feldmann, Vera Dietzgen, interview by Joshua J. Morris. Joseph Dietzgen Research (May 2, 2008)

- ^ Plekhanov, "Joseph Dietzgen"

- ^ Bakhurst, D. On Lenin’s Materialism and empiriocriticism. Stud East Eur Thought 70, 107–119 (2018)

- ^ "The Original Joseph Dietzgen Web Page". Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2006.

- ^ Lenin, V. "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder

- ^ Pannekoek, A. "Lenin as Philosopher" "Lenin as Philosopher". marxists.org.

- ^ "Stamp Name: ddrp-008-05". old-stamps.de. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

External links

[edit]- Joseph Dietzgen Archive

- Dietzgen Family History Page includes interviews with Dietzgen's granddaughter and 145 page typescript of Dietzgen's 1880-84 correspondence with his son

- Joseph Dietzgen's Philosophy

- Eugene Dietzgen Corporation History Page Archived October 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Works by Joseph Dietzgen at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joseph Dietzgen at the Internet Archive

- 1828 births

- 1888 deaths

- People from Hennef (Sieg)

- People from the Rhine Province

- German atheists

- Members of the International Workingmen's Association

- 19th-century German philosophers

- Marxist theorists

- Atheist philosophers

- Materialists

- American Marxists

- 19th-century atheists

- Burials at Forest Home Cemetery, Chicago