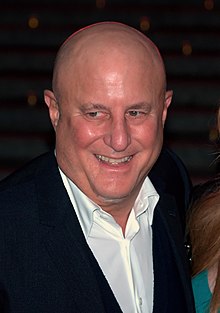

Ronald Perelman

Ronald Perelman | |

|---|---|

Perelman in 2009 | |

| Born | Ronald Owen Perelman January 1, 1943 Greensboro, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Education | Villanova University (BS) University of Pennsylvania (MBA) |

| Occupations |

|

| Employer | MacAndrews & Forbes |

| Spouses | Faith Golding

(m. 1965; div. 1984)Anna Chapman (m. 2010) |

| Children | 8 |

| Father | Raymond G. Perelman |

| Relatives | Jeffrey E. Perelman (brother) |

Ronald Owen Perelman (/ˈpɛrəlmən/; born January 1, 1943)[1] is an American banker, businessman, investor, and philanthropist.[2] MacAndrews & Forbes Incorporated,[3] his company, has invested in companies with interests in groceries, cigars, licorice, makeup, cars, photography, television, camping supplies, security, gaming, jewelry, banks, and comic book publishing. Perelman holds significant shares in companies such as Deluxe Entertainment, Revlon,[4] SIGA Technologies,[5][6] RetailMeNot,[7] Merisant, Scantron, Scientific Games Corporation,[8] Valassis, vTv Therapeutics[9] and Harland Clarke.[10] He previously owned a majority of shares in AM General, but in 2020 sold the majority of his shares in AM General along with significant works of art, in light of the impact of the economy on the high debt burdens many of his companies have from leveraged buyouts. In early 2020, Revlon, acquired by Perelman in the 1980s, undertook a debt deal.[11] Previously worth $19.8 billion in 2018, Perelman is, as of November 2022, worth $1.9 billion.[12]

Early life and education

[edit]Perelman was born in Greensboro, North Carolina, on January 1, 1943, the son of Ruth (née Caplan) and Raymond G. Perelman.[13][14] He was raised in a Jewish family in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, and is the grandson of Litvak (Lithuanian Jewish) immigrants.[15][16][17] With family members, he managed the American Paper Products Corporation. Raymond eventually left the company and bought Belmont Iron Works, a manufacturer of structural steel.[18]

Perelman graduated from The Haverford School in Haverford, Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania in 1962.[19]

From his father, Perelman learned the fundamentals of business.[20] By the time Ronald turned eleven years old he regularly sat in on board meetings of his father's company. A 2006 article published in the Forbes 400 discusses their rough relationship in detail.[21][13]

Perelman first attended the Villanova School of Business for one semester before transferring to the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, where he majored in business. He earned his MBA from Wharton in 1966.[22]

In September 2017, Forbes magazine named Perelman as one of the "100 Greatest Living Business Minds".[23]

Business career

[edit]Belmont Industries

[edit]Perelman's first major business deal took place in 1961 during his Freshman year at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He and his father bought the Esslinger Brewery for $800,000, then sold it three years later for a $1 million profit.[24]

Throughout Perelman's tenure at the Belmont Iron Works (later renamed Belmont Industries) he assisted his father on other deals. Their general strategy was to purchase a company, sell off superfluous divisions to reduce debt and generate profit, bring the company back to its core business, and either sell it or hang onto it for cash flow. In 1978, twelve years after Perelman formally joined Belmont Industries, he was the vice president but he still strove for more power and influence in the company. His father Raymond told him that he had no intention of stepping down anytime soon. Perelman resigned and moved to New York. The two barely spoke to one another for the next six years.[25]

MacAndrews & Forbes Incorporated

[edit]He orchestrated the purchase of Cohen-Hatfield Jewelers in 1978, his first deal as an independent investor free of his father's influence and took a loan from his wife, Faith Golding. Within a year, Perelman had sold all of the company's retail locations and reduced the company to its lucrative wholesale jewelry division, earning him $15 million.[26]

Perelman acquired MacAndrews & Forbes, a distributor of licorice extract and chocolate. He faced resistance from the management and investors who filed an unsuccessful lawsuit to prevent the acquisition, but Perelman prevailed. In 1983, Perelman started selling bonds to acquire the remaining 66% stake in MacAndrews & Forbes Group Inc. to take MacAndrews & Forbes Group Inc. private.[27]

Also in 1983, MacAndrews had acquired Technicolor Inc.[28] Despite the bond debt, in 1984, MacAndrews & Forbes purchased Consolidated Cigar Holdings Ltd. from Gulf & Western Industries, in addition to Video Corporation of America.[29][30] The Technicolor Inc. divisions were sold off and, in 1988, its core business was sold to Carlton Communications for 6.5 times the purchase price. Using the proceeds from the Technicolor division sell off, MacAndrews & Forbes purchased a 20 percent stake in Compact Video Inc., a television and film syndication company. Ronald Perelman's controlling buyout of Compact Video was in 1986.

In 1989, Perelman acquired New World Entertainment, with David Charnay's Four Star Television becoming a unit of Ronald Perelman's Compact Video, later that year. Ownership of Compact Video Inc. was increased to 40% in 1989 after the buyout of Four Star International.[31][32][29] After Compact shut down, its remaining assets, including Four Star, were folded into MacAndrews and Forbes Incorporated. In 1989, Perelman also acquired New World Entertainment with Four Star becoming a division of New World as part of the transaction. Four Star International was purchased through a golden parachute deal that was negotiated with David Charnay by Ronald Perelman after Charnay was notified of stock purchases made by Perelman in 1989.[33] By the end of 1989, MacAndrews refinanced the Holding companies' junk bonds for standard bank loans. The bulk of New World's film and home video holdings were sold in January 1990 to Trans-Atlantic Pictures, a newly formed production company founded by a consortium of former New World executives.[34]

His company MacAndrews & Forbes became a holding company with interests in a diversified portfolio of public and private companies and was still wholly owned by Perelman, who served as its chairman and chief executive officer. In 1989, one of the company's holdings was Marvel Comics, which under Perelman's watch declared bankruptcy; he sold off Marvel in 1997.[35] MacAndrews & Forbes's current holdings include Deluxe,[36] Revlon,[37] SIGA Technologies,[38] VTV,[39] and as of late 2019, 39% of Scientific Games.[40][41] However, as of Q3 2019, the company had hired Goldman Sachs to help review strategic alternatives for Revlon.[42]

He has also done deals with Revlon Corporation,[43] thrifts for $315 million and renamed it First Gibraltar Bank,[44][45] Coleman Company, Sunbeam Products,[46] and New World Entertainment.[47][48]

Morgan Stanley

[edit]On February 17, 2005, Perelman filed a lawsuit against Morgan Stanley.[49] Two facts were at issue: did Morgan Stanley know about the problems with Sunbeam, and was Perelman misled?[tone] After a five-week trial, the jury deliberated for two days, found in favor of Perelman, and awarded him $1.45 billion.[50] The damages stung particularly because Morgan Stanley passed up Perelman's offer to settle the case for $20 million.[51] Morgan Stanley maintained that the court case was improperly decided, citing the judge's decision to use Florida law over New York law and her decision to order the jury to consider Morgan Stanley guilty before the trial began.[52] In 2007, the courts of appeal reversed the judgement. The judges declared Perelman hadn't provided any evidence showing he'd suffered any actual damage as a result of Morgan Stanley's actions. Perelman appealed,[53] but found himself shot down by the Florida Supreme Court who dismissed it in a 5–0 decision.[54] Undeterred even after that setback, Perelman went back to the trial court and asked for the case to be reopened because the hiding of email evidence was "a classic example of fraud on the court". The trial court rejected his arguments, but as of January 2009, he is beseeching Florida's 4th Circuit to reopen the case.[55]

Bloomberg reported on September 18, 2020, that Perelman had sold his Gulfstream 650, as well as his 257-foot yacht.[56]

Philanthropy

[edit]Personal donations

[edit]Perelman was a funder of the election campaign of Donald Trump, giving US$125,000 to Trump Victory in September 2017.[57] In 2015, Perelman donated $500,000 each to Super PACs supporting the presidential candidacies of Lindsey Graham and Jeb Bush.[58]

In 1995, Perelman donated to Princeton University to create the Ronald O. Perelman Institute for Judaic Studies.[59][60] Other notable donations include $20 million to the University of Pennsylvania for naming rights to the quadrangle,[61] $10 million to New York University to create the Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology,[62] $4.7 million to Princeton University to create the Ronald Perelman Institute for Jewish Studies,[63] and $20 million to the Guggenheim Museum.[64] From 2006 through 2008, Perelman donated $63.5 million to causes including, but not limited to: Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Stand Up to Cancer (SU2C), World Trade Center Memorial Fund and Ford's Theatre, Carnegie Hall and the World Trade Center Memorial.[65] In February 2008, Perelman made a $50 million donation to the New York Presbyterian Hospital and Weill Cornell Medical Center to create the Ronald O. Perelman Heart Institute, and to provide vital financial aid to the Ronald O. Perelman and Claudia Cohen Center for Reproductive Medicine.[66][67]

Perelman serves as a member of the board of directors of the Police Athletic League of New York City, a nonprofit youth development agency serving inner-city children and teenagers. On June 3, 2011, Perelman was honored for his charitable contributions at the New York Police Foundation's 40th Anniversary Gala[68] at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City—an event that raised $2.3 million for charity.

Since 2013, Perelman donated $50 million to the NYU Langone Medical Center to create the Ronald O. Perelman Center for Emergency Services,[69] $25 million to the University of Pennsylvania to create a new Center for its Economics and Political Science Departments,[70][71] $100 million to the Columbia Business School, the graduate business school of Columbia University. The gift will be used to support the construction of new facilities in Manhattanville, including the Ronald O. Perelman Center for Business Innovation.[72][73] and donated $75 million to revive plans to build a performing arts center at the World Trade Center site.[74][75]

In May 2015, Perelman succeeded Sanford I. Weill as Chairman of Carnegie Hall.[2] and since 2010 he has also hosted annual benefits for the Apollo Theater, raising millions of dollars annually for the legendary venue.[76]

In August 2021, Princeton University announced that it would no longer name a newly constructed student dormitory for Perelman after the family foundation failed to make payments on a pledged $65 million donation.[77]

Controversy

[edit]Greenmail

[edit]In the late 1980s, Perelman was accused of engaging in greenmail.[78] "Greenmail" occurs when someone buys a large block of a company's stock and threatens to take over the company unless he is paid a substantial premium over his purchase price. In the case of someone with a reputation as a corporate raider, the mere act of buying up shares could send a company into a panic and investors into a buying frenzy.[79] Perelman insists he seriously intended to buy every corporation he bought into.[80]

He was first accused of greenmail in late 1986 during a run at CPC International when he bought 8.2% of CPC at around $75 a share and indirectly sold it back to CPC through Salomon Brothers a month later at $88.5 a share for a $40 million profit. Both CPC and Perelman denied it was greenmail despite appearances to the contrary, including what looked like an artificial price increase by Salomon shortly before they sold Perelman's shares.[81]

Another accusation of greenmailing levied against him was the best-known and stemmed from his attempt to purchase Gillette in November 1986. Perelman opened negotiations with a bid of $4.12 billion. Gillette responded with an unsuccessful lawsuit and public insinuations of insider trading. Perelman accumulated 13.8% of Gillette before he made what he would later call the worst decision he ever made and sold his stake to Gillette later that month for a $34 million profit. Gillette had put word out that Ralston Purina had agreed to buy a 20% block of stock, making any attempt by Perelman to buy Gillette much more difficult. Perelman decided to sell his share to Ralston Purina, but before he did so Gillette's executives called him up, asking if he'd sell his shares to them and they'd sell the shares to Ralston Purina. He sold his shares to Gillette and Ralston backed out of the deal.[82]

Panavision

[edit]In April 2001, M&F Worldwide bought Perelman's 83% stake in Panavision for $128 million. This would be unremarkable except that Perelman controlled M&F Worldwide and the price paid for his stake was four times market value. At the time, M&F Worldwide was a healthy company with an excellent balance sheet while Panavision was bleeding red ink. M&F Worldwide's other shareholders cried foul, alleging the only person who stood to benefit from the deal was Perelman and took their complaints to the courts.[83] Perelman insisted the deal was an excellent one and in the best interest of the shareholders because Panavision was well-positioned to profit from the move to digital cinematography.[84] The share price tumbled from six to three after the deal and reflected M&F Worldwide shareholders' lack of confidence.[85] Perelman tried to pacify M&F Worldwide's shareholders with a $15 million settlement, but the judge rejected it as grossly inadequate. Ultimately, Perelman agreed to undo the deal.[86]

Fred Tepperman

[edit]Perelman hired Fred Tepperman as his CFO after Tepperman left Warner Communications in 1985. Starting with Pantry Pride, Tepperman worked on every single business deal Perelman orchestrated throughout Tepperman's seven-year stint at MacAndrews & Forbes. Tepperman's tenure came to an abrupt end just after Christmas in 1991 when Perelman fired him for being derelict in his duties. Tepperman had been distracted, he claimed, by caring for his Alzheimer's-afflicted wife of 30 years. A clause in Tepperman's contract entitled him to a large portion of his salary and benefits in the event of an injury that prevented him from being able to work; Tepperman claimed he had suffered such an injury, albeit psychologically, as a result of the effect his wife's condition had on him. His demands totaled $30 million. That number stems partially from Tepperman's salary, which started at $275,000 and rose to $1.2 million in 1990[87] and partially from his large benefits package.[88] Perelman was quick to file a countersuit for fraud, claiming that Tepperman had sneakily changed the company's retirement plan in such a way that Tepperman would personally gain millions of dollars.[87] It took over three years for the case to make it to court. The case ended with a sealed settlement.[87]

Personal life

[edit]Marriages

[edit]Perelman has been married five times. He married Sterling Bank heiress Faith Golding in 1965 and they divorced in 1984. His marriage to gossip columnist Claudia Cohen lasted from 1985 to 1994. He married socialite Patricia Duff in 1995 and divorced in 1996. He was married to actress Ellen Barkin from 2000 to 2006. On October 13, 2010, Perelman married Dr. Anna Chapman, a Harvard University-educated psychiatrist.

Faith Golding

[edit]Perelman met his first wife, Faith Golding, in 1965 on a cruise to Israel. As the heir to a real-estate and banking fortune, she controlled personal wealth of around $100 million at the time of their marriage.[89] After they had adopted three children—Steven, Josh, and Hope—Faith gave birth to their fourth child, Debra. Their marriage lasted until 1984, when Faith discovered Perelman's ongoing affair with a local florist after a bill for a Bulgari bracelet arrived at their home, instead of Perelman's office. She further declared he had defrauded the owners of First Sterling Corporation (i.e. herself) by diverting thousands of dollars of company money into gifts for the florist. Faith made a very public spectacle of the divorce. Perelman responded by hiring Roy Cohn and flatly denying all her allegations. The pair quickly settled the divorce with an estimated payout to Faith in excess of $8 million.[90]

Claudia Cohen

[edit]

Perelman met his second wife, Claudia Cohen, in 1984 at Le Cirque. They had one daughter together, Samantha, in 1990. In August 1993, Ron filed for divorce.[91] Claudia left the marriage with well over $80 million.[91] In 2007, Claudia died after a secret seven-year battle with ovarian cancer. Perelman revealed in his eulogy at her funeral that he had known about her cancer from the beginning and privately commissioned a vaccine in his efforts to cure her.[92][93] He donated $20 million to the University of Pennsylvania to remodel what is now Perelman Quadrangle and, as part of that donation, had the option of renaming Logan Hall. His decision to change it to Cohen Hall dismayed some Penn faculty, alumni, and students.[94]

Patricia Duff

[edit]Patricia Duff was Perelman's third wife. The pair first met in a Paris hotel lobby when both were still married: Perelman to Cohen, and Duff to Mike Medavoy.[95] After Duff divorced Medavoy, Duff converted to Judaism[96] and married Perelman, on January 25, 1995. She gave birth to his fourth daughter, Caleigh Sophia, before the wedding took place.[97] When the marriage between Duff and Perelman disintegrated in 1996, custody over Caleigh became a major issue. Both Perelman and Duff wanted full custody and their prenuptial agreement did not address the subject of child support. Initially private, the divorce proceedings were opened to the public at the request of Duff.[98] Neither party emerged with their reputations unscathed. The court psychiatrist found Duff to be paranoid and narcissistic and Perelman to have serious anger management issues,[99] Perelman caught a great deal of flak for testifying that it cost about $3 a day to feed his daughter,[100] and both sides alleged physical abuse by the other party.[101] The judge's sealed decision means the public will never know the exact results of the case,[98] but it's known that neither party actually won. Perelman is Caleigh's legal guardian, but Patricia has extensive visitation rights.[102]

Ellen Barkin

[edit]

Perelman met his fourth wife, actress Ellen Barkin, at a Vanity Fair Oscar after-party in 1999.[103] After slightly more than a year of courtship, the two married in June 2000. All accounts indicate their five-year marriage was a stormy one. Much of the friction arose due to Barkin's acting career and her attendant travel schedule. Perelman filed and obtained a divorce in early 2006. The press soundly mocked Perelman for his actions, the speed and timing of which suggested his real motivation was to avoid a clause in his prenuptial that would raise the amount in alimony he owed Barkin if he waited a few days longer. Depending on the source used, Barkin's yearly alimony ranges from $2 million to $3 million, and the total payout ranged from $20 million to $65 million.[104] In late 2007, the pair exchanged lawsuits. Part of the divorce settlement required Perelman to invest several million dollars in a film production company Barkin and her brother George (an aspiring screenwriter) had started. Perelman made only one of the payments, claiming that there was no evidence the two were actually producing films. Barkin sued for her money while Perelman counter-sued, alleging Barkin and her brother had looted the film company for themselves.[105] Four years later the lawsuits ended in a confidential settlement.[106]

Anna Chapman

[edit]Perelman began dating psychiatrist Dr. Anna Chapman, in mid-2006.[107] In late November 2010, the couple celebrated the birth of their son, Oscar. The couple later had a second child, Ike, in May 2012.

Judaism

[edit]Judaism has had a strong influence on Perelman's life. He grew up in a Conservative household. The temple he went to growing up was a Reconstructionist temple,[108] and his father donated millions to Conservative causes.[109] He had a religious reawakening at the age of eighteen while on a family trip to Israel:[102]

I felt not just this enormous pride at being a Jew; I felt this enormous void at not being a better Jew. So I decided then to begin being a better Jew. As soon as I got married, we kept a kosher house, we became much more observant. We moved to New York shortly thereafter and joined an Orthodox synagogue and the kids grew up with much more Judaism surrounding them than I ever did.[102]

Today, he strictly observes the Jewish Sabbath, spends three hours every Saturday in prayer,[110] keeps a kosher home,[111] and donates millions to Jewish groups and causes, particularly the Chabad-Lubavitch sect.[110] He does not consider himself to be a member of Lubavitch. He supports them because he thinks they are Judaism's best chance for surviving and thriving in modern society.[102]

Homes

[edit]

Perelman is the owner of "Près Choisis" (now called "The Creeks"), a 40-room Mediterranean-style villa on Georgica Pond in East Hampton, Long Island. It was built in 1899 by the artists Adele and Albert Herter. In October 2018 a fire spread from the attic and burned for several hours. Insurers paid around $141 million for fire damage, but rejected claims of damage to five paintings insured for a total of $410 million. As of 2022 April 11[update], Perelman's suit against the insurers is before the New York Supreme Court.[112]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "UPI Almanac for Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019". United Press International. January 1, 2019. Archived from the original on September 2, 2019. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

businessman Ron Perelman in 1943 (age 76)

- ^ a b Pogrebin, Robin (May 2015). "Ronald Perelman". The New York Times. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ^ "Ronald O. Perelman: MacAndrews and Forbes Bio". MAF. January 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ Perino, Marissa (April 15, 2019). "The 25 richest people in New York, ranked". Business Insider. Insider Inc. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Griffin, Drew (December 9, 2011). "E-mails questioned huge contract for firm with ties to Obama administration". CNN. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Elstein, Aaron (January 21, 2011). "Ron Perelman vs. Donald Drapkin". crainsnewyork.com. Crain's New York Business. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ "RetailMeNot is getting bought for $630 million by one of billionaire Ron Perelman's companies". Business Insider. Insider Inc. April 10, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ Stutz, Howard. "Perelman's $27 million in stock purchases viewed as way to off-set Scientific Games' sour 2018". cdcgamingreport.com. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ "Billionaire Ronald Perelman buys more shares of vTv Therapeutics". Biz Journals. American City Business Journal. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Bloomberg Billionaires Index". Bloomberg. May 29, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ "Perelman Begins Unwinding Multibillion Dollar Empire With Sale". Bloomberg.com. July 22, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ Block, Fang. "Billionaire Businessman Ronald O. Perelman's Design Collection Heads to Auction". www.barrons.com. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Hack 1996 pp. 1–3

- ^ Current Biography Yearbook. H. W. Wilson Co. January 1, 1992. ISBN 9780824201289 – via Google Books.

- ^ Abigail Pogrebin, Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish, (Broadway 2007)

- ^ "Don't Mess With Me - Forbes.com". www.forbes.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2005. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ DiStefano, Joseph N. (January 15, 2019). "Raymond G. Perelman, master investor and philanthropist, dies at 101". www.inquirer.com. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art – Information: Our Future: Perelman Building: Raymond G. and Ruth Perelman". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ "Haverford Grad Ronald Perelman Instigated Hostile Takeover Era, But Rules Are Now Changing Once Again". montco.today. November 18, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- ^ Ramirez, Anthony (2006). "The Year's 50 Most Fascinating Business People Ron Perelman Revlon's Striving Makeover Man". Fortune. Time Inc. Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ^ Blankfeld, Keren (2006). "Exclusive Interview: Billionaire Ronald Perelman With His Dad". Forbes. Forbes LLC. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ Jeff Gordinier (2006). "Perelman: Man behind the paln". Daily Pennsylvanian. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^ "Forbes List "100 Greatest Living Business Minds"". Forbes. September 2017. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ Hack 1996 pp. 4–9

- ^ Hack 1996 p. 9

- ^ Hack 1996 pp. 10–12

- ^ Hack 1996 p. 13

- ^ Al Delugach (September 10, 1988). "British Concern Agrees to Buy Technicolor Inc. : Carlton to Pay About $780 Million for the Movie-Film Processor". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings Inc". Funding Universe. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- ^ "Cigar Aficionado Interview with Billionaire Ron Perelman". Cigar Aficionado.

- ^ CROUCH, GREGORY (December 22, 1987). "Reasons Emerge for the Liquidation of Compact Video". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ "Perelman's Not Out of the Game Just Yet". Los Angeles Times. July 18, 1996. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ Fineman, Josh (January 26, 1995). "Perelman: Man behind the plan". The Daily Pennsylvanian. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ "New World Deal". Los Angeles Times. January 4, 1990. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ "Marvel Reaches Agreement to Emerge from Bankruptcy". The New York Times. July 11, 1997. p. D3. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Deluxe". MacAndrews & Forbes.

- ^ "Revlon". MacAndrews & Forbes.

- ^ "SIGA Technologies". MacAndrews & Forbes.

- ^ "vTv Therapeutics LLC - MacAndrews & Forbes Incorporated".

- ^ "Scientific Games". MacAndrews & Forbes.

- ^ “Billionaire Financier Ron Perelman Boosts Stake in Scientific Games, Sparks Massive Rally in Stock.” Casino.org. 23 Sept 2019.

- ^ Yerak, Becky (August 15, 2019). "Revlon Exploring Strategic Alternatives With Help From Goldman Sachs". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ Stevenson, Richard (November 5, 1985). "Pantry Pride Control of Revlon Board Seen Near". New York Times. p. D5. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ Hayes, Thomas (December 29, 1988). "Talking Deals; A Veil of Secrecy In Texas Rescues". New York Times. p. D2.

- ^ Ladendorf, Kirk (April 3, 1989). "A bank by any other name . . . must be in Austin // Confusion, lawsuits greet the changes made of necessity". Austin American Statesman. p. 12.

- ^ "MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings Inc". Answers.com. 1999. Archived from the original on March 2, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ^ Hack 1996 pp. 140–150

- ^ Raviv, Dan (2002). "Comic Wars". Random House. Archived from the original on April 22, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Court TV Online – Coleman vs. Morgan Stanley". Court TV. 2005. Archived from the original on March 16, 2006. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ Susan Rosser, Bo (2005). "Jury awards Perelman $850 million in damages from Morgan Stanley". Court TV. Archived from the original on November 1, 2006. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ Cramer, James J. "Morgan Stanley CEO Phil Prucell's People Problem". New York. New York Media, LLC. Archived from the original on June 21, 2007. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ Jones, Carl (2005). "Law.com – Morgan Stanley: 'Record Is Clear' That Florida Judge Erred". Daily Business Review. Archived from the original on June 23, 2007. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ Bruno, Joe Bel (2007). "ABC News: Morgan Stanley-Perelman Judgment Flipped". ABC News. Disney-ABC Television Group. Archived from the original on March 28, 2007. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ^ Feeley, Jef; Harper, Christine (2007). "Perelman Loses Appeal of Morgan Stanley Jury Award". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- ^ Feeley, Jef; Milford, Phil (January 5, 2009). "Perelman Seeks to Reopen Case Against Morgan Stanley". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ "Perelman Selling Almost Everything as Pandemic Roils His Empire". Bloomberg.com. September 18, 2020 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- ^ Tindera, Michela (April 17, 2020). "Here Are The Billionaires Backing Donald Trump's Campaign". Forbes.com. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- ^ "Million-Dollar Donors in the 2016 Presidential Race". The New York Times. August 25, 2015. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ Mento, Maria Di (December 10, 2018). "Billionaire Ron Perelman and His Daughter Debra Give Princeton $65 Million: Gifts Roundup". philanthropy.com. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "Perelman Institute for Judaic Studies". Princeton.edu.

- ^ Schweiger, Tristan (2000). "Trustees visit Perelman Quad opening". Daily Pennsylvanian. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^ Myers, Steven Lee (1991). "Chronicle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017.

- ^ Myers, Steven Lee (1995). "Chronicle". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2007.

- ^ Rosebaum, Lee (2003). "The Guggenheim regroups: The Story Behind the Cutbacks: in financial crisis, and with its downtown NYC expansion plan deferred or defunct, the Guggenheim museum continues to explore ambitious new global projects". Art in America. Archived from the original on November 5, 2004. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^ "America's Most Generous Donators". The Chronicle of Philanthropy. 2006. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^ "Chronicle". Faces of Philanthropy. 2009.

- ^ "Ron Perelman Is Bringing Performing Arts to the World Trade Center". Town and Country. 2017.

- ^ "Scene Last Night: Ron Perelman, Ray Kelly, Jon Bon Jovi, NYPD". Bloomberg News. 2011. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- ^ "Chronicle". Philanthropy News Digest. 2013.

- ^ "Chronicle". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia Media Network. 2013. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Exclusive Interview: Billionaire Ron Perelman with His Dad". Forbes.com. 2011.

- ^ yz (May 1, 2013). "Ronald O. Perelman Pledges $100 Million Toward Manhattanville". Archived from the original on June 15, 2013.

- ^ "Perelman Pledges $100 Million to Columbia Business School". New York Times (DealBook). May 2, 2013. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Ronald Perelman Donates $75 Million for Arts Complex at World Trade Center Site". The New York Times. June 30, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ "Perelman Donates $75 Million for Arts Complex at World Trade Center Site". Town and Country. May 8, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ^ Blankfeld, Keren (2011). "Chronicle". Forbes.

- ^ "Perelman name removed from Residential College 7".

- ^ Atlas, Riva (2000). "The Perils of Perelman". Institutional Investor. 34 (3): 54.

- ^ Hack 1996 pp. 80–82, 99

- ^ Hagedom, Ann (March 9, 1987). "Possible Revlon Buyout May Be Sign Of a Bigger Perelman Move in Works". Wall Street Journal. p. 1.

- ^ Sandler, Linda (November 7, 1986). "Big CPC Trade Has Money Managers Asking If It Was Actually Greenmail for Perelman". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. p. 1.

- ^ A lengthy Q&A interview from 1995. Shanken, Marvin R. "Cigar Stars". Cigar Aficionado. Archived from the original on February 25, 2007. Retrieved February 2, 2007.

- ^ Bary, Andrew (September 27, 1987). "Perelman's Price". Barron's. Vol. 80, no. 47. p. 45.

- ^ Atlas, Riva D (December 17, 2000). "Perelman's Endless (and Costly) Love". The New York Times. p. C1.

- ^ Bary, Andrew (August 13, 2001). "Perelman's Plight". Barron's. Vol. 81, no. 3. Dow Jones & Company. p. 17.

- ^ Bary, Andrew (August 5, 2002). "Sour Candy". Barron's. Vol. 82, no. 31. Dow Jones & Company. p. 13.

- ^ a b c Hack 1996 pp. 126, 185–219

- ^ Jehl, Douglas (June 28, 1995). "An Ill Wife, A Tough Boss And a Lawsuit". The New York Times. p. D1.

- ^ Hack 1996 pp. 5–6

- ^ Hack 1996 pp. 23–28

- ^ a b Hack 1996 pp. 146, 149

- ^ In March 2008, Perelman decided to change the name of Logan Hall at the University of Pennsylvania to Cohen Hall. He donated $20 million to the University and, as part of that gift, was permitted to rename Logan Hall.Friedman, Roger (June 19, 2007). "Claudia Cohen: Funeral for a Friend". Fox411. Fox News. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ Wu, Cecily. Logan Hall to become Claudia Cohen Hall Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Pennsylvanian. March 19, 2008

- ^ Wu, Cecily. What's in a name? A lot, say profs, alums Archived March 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Pennsylvanian. March 27, 2008

- ^ Byron, Christoper M. (2004). Testosterone Inc. Tales of CEOs Gone Wild. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 183. ISBN 0-471-42005-0.

- ^ Jewish Journal: "A Battle With No Winners" October 21, 1999

- ^ Byron, Christoper M. (2004). Testosterone Inc. Tales of CEOs Gone Wild. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 199. ISBN 0-471-42005-0.

- ^ a b Martinez, Andres (2005). "Billionaire a name in gossip columns as often as business section". Court TV. Archived from the original on March 16, 2006. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ McShane, Larry (1999). "Perelman v. Duff: A divorce of the vanities". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 27, 2005. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ Oreklin, Michele (February 1, 1999). "People". Time. Time Inc. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ Gregorian, Dareh (December 9, 1998). "Perelman custody case gets physical". New York Post. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Pogrebin, Abigail (2005). Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish. New York: Broadway. pp. 84–91. ISBN 978-0-7679-1612-7.

- ^ Susan Dominus (2005). "Ms Barkin and the billionaire". The Irish Independent. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- ^ Gray, Geoffrey (2006). "Ron Perelman vs. Ellen Barkin: Scenes From a Broken Marriage". New York Magazine. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- ^ Hurtado, Patricia (2008). "Perelman Sues Ex-Wife Barkin, Claiming She Took Funds". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on April 7, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2007. Archive link is dead.

- ^ Martinez, Jose (January 18, 2011). "Ellen Barkin and billionaire ex Ron Perelman settle nasty legal battle over film company". New York Daily News.

- ^ http://wallstfolly.typepad.com/wallstfolly/2006/11/ellen_barkin_to.html#comments Archived July 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine ...Barkin looked over at Perelman's table, saw his dinner date Anna Chapman, and told the blond psychotherapist...

- ^ Beth Sholom Synagogue, Elkins Park, PA, The Nahum Goldmann Museum of the Jewish Diaspora. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ Tobin, Jonathan S. "If you build it, will they come?", Jerusalem Post, 2006-03-27, p. 13.

- ^ a b Powell, Michael (1998). "Perelman Power". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^ Ross, Lillian (2005). "Ellen Barkin At Home". The New Yorker. Conde Nast. Archived from the original on June 6, 2005. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- ^

- Kinsella, Eileen (October 26, 2022). "Mega-Collector Ronald Perelman Is Suing to Recover $410 Million for Art He Says Lost 'Oomph' After a Fire at His Hamptons Estate. His Insurance Companies Say It Looks Fine". Artnet News. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- Moynihan, Colin (November 15, 2022). "Did Five Paintings Lose Their 'Oomph'? It's a $410 Million Question". The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- "Search All New York State Civil Supreme Court Cases". Index Number 654742/2020.

General and cited references

[edit]- Hack, Richard (1996). When Money Is King: How Revlon's Ron Perelman Mastered the World of Finance to Create One of America's Greatest Business Empires, and Found Glamour, Beauty, and the High Life in the Bargain. Beverly Hills, CA: Dove Books. ISBN 0-7871-1033-7 – via Internet Archive. [This unauthorized biography was reviewed by Perelman before publication.]

- 1943 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American businesspeople

- 20th Century Studios people

- 21st-century American businesspeople

- 21st-century American philanthropists

- American billionaires

- American chairpersons of corporations

- American chief executives of financial services companies

- American chief executives in the media industry

- American financiers

- American nonprofit chief executives

- American Orthodox Jews

- American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- American retail chief executives

- American stock traders

- American tobacco industry executives

- American venture capitalists

- Baalei teshuva

- Businesspeople from Pennsylvania

- Businesspeople from Philadelphia

- Corporate raiders

- Drexel Burnham Lambert

- Haverford School alumni

- Jewish American bankers

- Marvel Comics people

- New York (state) Republicans

- People from Cheltenham, Pennsylvania

- Recipients of the Legion of Honour

- Wharton School alumni