Sligo

Sligo

Sligeach | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| |

| Coordinates: 54°16′00″N 8°29′00″W / 54.2667°N 8.4833°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Connacht |

| County | County Sligo |

| Barony | Carbury |

| Dáil constituency | Sligo–Leitrim |

| EU Parliament | Midlands–North-West |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10.3 km2 (4.0 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 13 m (43 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 20,608 |

| • Density | 2,000/km2 (5,200/sq mi) |

| Eircode (Postcode) District | F91 |

| Irish Grid Reference | G685354 |

| Dialing code | +353 71 |

| Website | www |

Sligo (/ˈslaɪɡoʊ/ SLY-goh; Irish: Sligeach [ˈʃl̠ʲɪɟəx], meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of 20,608 in 2022, it is the county's largest urban centre (constituting 29.5% of the county's population) and the 24th largest in the Republic of Ireland.[2][3]

Sligo is a commercial and cultural centre situated on the west coast of Ireland. Its surrounding coast and countryside, as well as its connections to the poet W. B. Yeats, have made it a tourist destination.

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Sligo is the anglicisation of the Irish name Sligeach, meaning "abounding in shells" or "shelly place". It refers to the abundance of shellfish found in the river and its estuary, and from the extensive shell middens in the vicinity.[4][5] The river now known as the Garavogue (Irish: An Gharbhóg), perhaps meaning "little torrent", was originally called the Sligeach.[6] It is listed as one of the seven "royal rivers" of Ireland in the ninth century AD tale The Destruction of Da Dergas Hostel. The river Slicech is also referenced in the Annals of Ulster in 1188.[6]

The Ordnance Survey letters of 1836 state that "cart loads of shells were found underground in many places within the town where houses now stand". The whole area, from the river estuary at Sligo, around the coast to the river at Ballysadare Bay, is rich in marine resources which were utilised as far back as the Mesolithic period.

Early history

[edit]The importance of Sligo's location in prehistory is demonstrated by the abundance of ancient sites close by and even within the town. For example, Sligo town's first roundabout was constructed around a megalithic passage tomb at Abbeyquarter North in Garavogue Villas.[7] This is an outlier of the large group of monuments at Carrowmore on the Cúil Iorra Peninsula on the western outskirts of the town. The area around Sligo town has one of the highest densities of prehistoric archaeological sites in Ireland, and is the only place in which all classes of Irish megalithic monuments are to be found together. Knocknarea mountain, capped by the great cairn of Miosgan Maeve, dominates the skyline to the west of the town. Cairns Hill on the southern edge of the town also has two very large stone cairns.

Excavations for the National Roads Authority (NRA) for the N4 Sligo Inner Relief Road in 2002 revealed an early Neolithic causewayed enclosure. Built around 4000 B.C., the Magheraboy causewayed enclosure is located on high ground overlooking the town from the south. This is the oldest causewayed enclosure so far discovered in Britain or Ireland.[8] It consists of a large area enclosed by a segmented ditch and palisade, and was perhaps an area of commerce and ritual. These monuments are associated with the coming of agriculture and hence the first farmers in Ireland. According to archaeologist Edward Danagher, who excavated the site, "Magheraboy indicates a stable and successful population during the final centuries of the fifth millennium and the first centuries of the fourth millennium BC".[9] Danagher's work also documented a Bronze Age Henge at Tonafortes (beside the Carraroe roundabout) on the southern outskirts of Sligo town.

Sligo Bay is an ancient natural harbour, being known to Greek, Phoenician and Roman traders as the area is thought by some to be the location marked as the city of Nagnata on Claudius Ptolemy's second century A.D. co-ordinate map of the world.[10] During the early medieval period, the site of Sligo was eclipsed by the importance of the great monastery founded by Columcille 5 miles to the north at Drumcliff. By the 12th century, there was a bridge and a small settlement in existence at the site of the present town.

Medieval history

[edit]The Norman knight Maurice Fitzgerald, the Justiciar of Ireland, is generally credited with the establishment of the medieval European-style town and port of Sligo, building Sligo Castle in 1245. The annalists refer to the town as a sraidbhaile ('street settlement') which seems to have consisted of the castle and an attached defensive bawn in the vicinity of Quay street. A Dominican Friary (Blackfriars) was also founded by Maurice Fitzgerald and the King of Connacht, Felim mac Cathal Crobderg Ua Conchobair, in 1253. This was accidentally destroyed by fire in 1414, and was subsequently rebuilt in its present form by Tighernan O’Rourke. Norman hegemony was, however, not destined to last long in Sligo. The Norman advance was halted in Sligo after the battle of Credran Cille in 1257 at Ros Ceite (Rosses Point) between Godfrey O'Donnell, Lord of Tirconnell, and Maurice Fitzgerald. Both commanders were mortally wounded in single combat. The Norman invasion of Tír Chonaill was abandoned after this. In 1289 a survey indicates there were 180 burgesses in the town. The Normans had laid a foundation that was to last.

The town is unique in Ireland in that it is the only Norman-founded Irish town to have been under almost continuous native Irish control throughout the Medieval period. Despite Anglo-Norman attempts to retake it, it became the administrative centre of the O'Conor Sligo (O'Conchobar Sligigh) confederation of Iochtar Connacht (Lower Connacht) by 1315 AD. Also called Clan Aindrias, the O 'Conors were a branch of the O'Conchobar dynasty of Kings of Connacht. It continued to develop within the túath (Irish territory) of Cairbre Drom Cliabh becoming the effective centre of the confederation of túatha. The other Irish túatha subject to here were Tír Fhíacrach Múaidhe, Luighne Connacht, Tir Olliol and Corann. Throughout this time Sligo was under the system of Fénechus (Brehon) law and was ruled by the Gaelic system of an elected Rí túath (territory king/lord), and an assembly known as an oireacht.

Through competition between Gaelic dynasties for the lucrative port duties of Sligo, the town was burned, sacked or besieged approximately 49 times during the medieval period, according to the annals of Ireland.[11] These raids seem to have had little effect on the development of the town, as by the mid-15th century the town and port had grown in importance. It traded with Galway, Bristol, France and Spain. Amongst the earliest preserved specimens of written English in Connacht is a receipt for 20 marks, dated August 1430, paid by Saunder Lynche and Davy Botyller, to Henry Blake and Walter Blake, customers of "ye King and John Rede, controller of ye porte of Galvy and of Slego".

Sligo continued under Gaelic control until the late 16th century when, during the Elizabethan conquest, it was selected as the county town for the newly shired County of Sligo. An order was sent by the Elizabethan Government to Sir Nicholas Malby, Knight, wanting him to establish "apt and safe" places for the keeping of the Assizes & Sessions, with walls of lime & stone, in each county of Connacht, "judging that the aptest place be in Sligo, for the County of Sligo…"[12] The walls were never built.

17th and 18th centuries

[edit]Sligo Abbey, actually a Dominican Friary, although a ruin, is the only medieval building left standing in the town. Much of the structure, including the choir, carved altar (the only one in situ in Ireland) and cloisters, remains. When Sir Frederick Hamilton's Parliamentarian soldiers partially sacked Sligo in 1642, the Friary was burned and many friars killed.

During the Williamite War (1689–91) the town was fought over between the Jacobite Irish Army loyal to James II and Williamite forces. Patrick Sarsfield was able to capture the town and repulsed a Williamite attack to retake it; however, Sligo was later surrendered to forces under the command of Arthur Forbes, 1st Earl of Granard.

In 1798, a mixed force of the Limerick Militia, Essex Fencibles and local yeomanry under a Colonel Vereker[13] were defeated at the battle of Carricknagat at Collooney by the combined Irish and French forces under General Humbert. A street in the town is named after the hero of this battle Bartholomew Teeling. The Lady Erin monument at Market Cross was erected in 1899 to mark the centenary of the 1798 Rebellion.[14]

19th century

[edit]The town suffered badly from a cholera outbreak in 1832. Scholars speculate that Bram Stoker, whose mother Charlotte Blake Thornley was probably (there are no records and the family lived in both Sligo and Ballyshannon)[15] born in Sligo in 1818[16] and experienced the epidemic first hand, was influenced by her stories when he wrote his famous novel, Dracula. The family lived on Correction Street in the town. After fleeing to Ballyshannon, Charlotte wrote:

At the end of that time, we were able to live in peace till the plague had abated and we could return to Sligo. There, we found the streets grass-grown and five-eighths of the population dead. We had great reason to thank God who had spared us.[15]

— Charlotte Thornley Stoker

The Great Famine between 1847 and 1851 caused over 30,000 people to emigrate through the port of Sligo.[17] On the Quays, overlooking the Garavogue River, is a cast bronze memorial to the emigrants. This is one of a suite of three sculptures commissioned by the Sligo Famine Commemoration Committee to honour the victims of the Great Famine.

A plaque in the background tells one family's sad story:

I am now, I may say, alone in the world. All my brothers and sisters are dead and children but yourself... We are all ejected out of Mr. Enright's ground... The times was so bad and all Ireland in such a state of poverty that no person could pay rent. My only hope now rests with you, as I am without one shilling and as I said before I must either beg or go to the poorhouse... I remain your affectionate father, Owen Larkin. Be sure answer this by return of post.

— 'Letter to America, 2 January 1850'

20th century

[edit]The early years of the century saw much industrial unrest as workers in the Port of Sligo fought for better pay and conditions. This resulted in two major strikes, in 1912 and, in 1913 the prolonged Sligo dock strike. Both ended in victory for the workers.

Sligo Town was heavily garrisoned by the British Army during the War of Independence. For this reason IRA activity was limited to actions such as harassment, sabotage and jailbreaks. At various times during the war, prominent Republicans were held at the Sligo Gaol. The commander of IRA forces in Sligo was Liam Pilkington.

Arthur Griffith spoke in April 1922 on the corner of O'Connell Street and Grattan Street. To this day it is known as Griffith's Corner.[citation needed] During the Civil War, Sligo railway station was blown up by Anti-Treaty forces on 10 January 1923.[18]

In 1961, St. John the Baptist's Church became a cathedral of the Diocese of Kilmore, Elphin and Ardagh after St. Mary's Cathedral in Elphin was abandoned, being destroyed by a storm four years previously.

Geography

[edit]

Situated on a coastal plain facing the Atlantic Ocean, Sligo is located on low gravel hills on the banks of the Garavogue River between Lough Gill and the estuary of the Garavogue river leading to Sligo Bay. The town is surrounded on three sides by an arc of mountains, with the Ox Mountain ridges of Slieve Daeane and Killery Mountain to the southeast bordering Lough Gill. The flat topped limestone plateaux of Cope's, Keelogyboy and Castlegal Mountains to the north and northeast and the singular hill of Knocknarea with its Neolithic cairn to the west and the distinctive high plateau of Benbulben to the north.

Sligo is an important bridging point on the main north–south route between Ulster and Connacht. It is the county town of County Sligo and is in the Barony of Carbury (formerly the Gaelic túath of Cairbre Drom Cliabh). Sligo is the diocesan seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Elphin. It is in the Church of Ireland Diocese of Kilmore, Elphin and Ardagh.

County Sligo is one of the counties that make up the province of Connacht. The county is part of the Border Region due to the fact that part of North Sligo is relatively close to 'the Border'. The Border Region in the Republic of Ireland has a population of over 500,000 people and consists of the counties of Cavan, Donegal, Leitrim, Louth and Monaghan.[19]

Architecture

[edit]The town consists of a medieval core street layout, but with mainly 19th-century buildings, many of which are of architectural merit.[20] The town has a High Street which descends from the south of the town and terminates in a market flare at the Market Cross, a pattern typical of Norman street layouts. Here it meets the east west road leading from the Abbeyquarter on the east side to St. Johns Cathedral to the west. This seems to have been the first street laid out in the town. Burgage plots of Norman origin are also evident in the long narrow property boundaries typical of the centre of the town.[20]

The only surviving medieval building is Sligo Holy Cross Dominican Friary built in 1252. An arched tower and three sided cloister of the Abbey Church still survive. The next oldest extant building is the Cathedral of St Mary the Virgin and St. John the Baptist on John Street. The current building dates from 1730 when it was designed by the German architect Richard Cassels who was visiting to design Hazelwood House. The cathedral contains four memorials to the Pollexfen family, maternal relatives of W. B. Yeats.[21]

In the nineteenth century, Sligo experienced rapid economic growth and therefore architectural change was rapid.[20] This was marked by the erection of many public buildings. These include Sligo Town Hall, designed by William Hague in a Lombardo-Romanesque style. Sligo Courthouse on Teeling street is an asymmetrical Neo-Gothic building designed by Rawson Carroll and built in 1878. The Gilooly Memorial Hall is an austere building on Temple Street built as a memorial to the Temperance campaigner Bishop Gillooly. His statue above the door bears the inscription "Ireland sober, is Ireland free". The Model School, now the Model Arts & Niland Gallery, was built by James Owen of the Board of Works to provide education to all denominations between 1857 and 1863, it was to serve as a model for other schools throughout the country.[22]

The former Batchelors factory on Deep Water Quay is an industrial building which was built in 1905 as a maize mill and grain silo, and used an innovative construction method invented by François Hennebique in 1892. It is one of the earliest examples of its type in Ireland.[23]

Climate

[edit]Sligo's climate is classified, like all of Ireland, as temperate oceanic. It is characterised by high levels of precipitation and a narrow annual temperature range. The mean yearly temperature is 9.4 degrees Celsius (49 degrees Fahrenheit). The mean January temperature is 5.2 °C (41 °F), while the mean July temperature is 15.3 °C (60 °F). On average, the driest months are April to June while the wettest months are October to January.

Rainfall averages 1131 mm (44.5 in) per year. The high rainfall means Sligo is in the temperate rainforest biome, examples of which exist around Lough Gill.[24] The lowest temperature ever recorded in Ireland was −19.1 °C (−2.4 °F) at Markree Castle, County Sligo, on 16 January 1881.

| Climate data for Markree Castle, County Sligo (1981–2010 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

14.9 (58.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

7.3 (45.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 130.8 (5.15) |

91.6 (3.61) |

108.9 (4.29) |

77.9 (3.07) |

81.4 (3.20) |

82.2 (3.24) |

93.0 (3.66) |

101.5 (4.00) |

104.4 (4.11) |

134.3 (5.29) |

128.4 (5.06) |

125.7 (4.95) |

1,260.1 (49.61) |

| Source: Met Éireann[25] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

Sligo had a population of 19,199 in 2016 and 20,608 in 2022, a growth of 7.3% according to the census.[26]

From the 2016 population, 9,238 were males and 9,961 females. Irish citizens made up 85.1% of the population with Polish (886 persons or 5.5%) as the next largest minority, followed by people from countries outside the EU (753 persons or 4.1%).[27]

6,299 persons could speak the Irish language and of these 1,639 spoke the language daily but only within the education system. 3,117 persons spoke a language other than Irish or English at home and, of these, 438 could not speak English well or at all. Polish was the most common foreign language spoken at home, with 980 speakers.[27]

Religion

[edit]

In the 2016 census, 14,428 residents identified their religion as Roman Catholic. A further 2,102 were adherents of other stated religions;[a] 1,959 persons indicated that they had no religion.[27]

Sligo is located in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Elphin. The main church of the diocese is the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception which is located on Temple Street. Other Catholic churches in the town are St. Anne's Church, Cranmore[28] and St. Joseph's Church, Ballytivnan.[29]

The town is also part of the Church of Ireland United Diocese of Kilmore, Elphin and Ardagh. The primary church in the diocese is the St John the Baptist Cathedral, Sligo which is located on John Street. Sligo Presbyterian Church is located on Church Street and Sligo Methodist Church is located on Wine Street. There is also a small Baptist church at Cartron Village, Rosses Point Road.

The Sligo-Leitrim Islamic Cultural Centre (SLICC) is located on Mail Coach Road.[30] The Indian Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church meets at the St. Johns Hospital Chapel, Benbullen Rehabilitation Unit, Ballytivan.[31]

Economy

[edit]

Sligo is in the Northern and Western Region, a NUTS 2 region classified as an underdeveloped "region in transition" by the EU Commission.[32] This is an area where GDP is from 75% to 90% of the EU average. It is entitled to funding from European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Operational Programmes, which are administered by the Northern and Western Regional Assembly. Sligo Town is part of the NUTS 3 Border Region, which recognises that part of north County Sligo is relatively close to the border with Northern Ireland. A study by the European Committee of the Regions found that the Border Region was the most exposed in Europe to the economic effects of Brexit.

Sligo is a major services and shopping centre within this region. As of 2016 the service sector is the primary employment sector in the county, employing 18,760 (71.7%) of workforce. Industry and construction makes up 17% (4,427) of employment, and agriculture, forestry and fishing 7.2% (1,868). The total number employed is 26,002. 3,843 people are employed in agency assisted (IDA) companies. Sligo borough labour catchment as of 2016 is 21,824.[33] 92% of enterprises in Sligo are micro-enterprises of 10 or fewer employees.

Sligo has traditionally been a centre for the tool-making industry.[clarification needed]

The pharmaceutical industry is significant with several companies producing goods for this sector,[34] including Abbott (Ireland) Ltd, which is among the largest employers in Sligo.[35]

Development has occurred along the River Garavogue with the regeneration of J.F.K. Parade (2000), Rockwood Parade (1993–1997), and The Riverside (1997–2006), as well as two new footbridges over the river, one on Rockwood Parade (1996) and one on The Riverside (1999).[citation needed] Sligo has a variety of independent shops and shopping malls. There is a retail park in Carraroe, on the outskirts of Sligo.[36]

Culture

[edit]

The culture of County Sligo, especially of North Sligo, was an inspiration on both poet and Nobel laureate W. B. Yeats and his brother, the artist and illustrator Jack Butler Yeats. A collection of Jack B. Yeats's art is housed in The Niland Gallery, part of the Model centre on The Mall in Sligo.[37] The Yeats Summer School takes place every year in the town.[38]

Sligo town has connections with Goon Show star and writer Spike Milligan, whose father was from Sligo, and a plaque was unveiled at the former Milligan family home on Sligo's Holborn Street.[39]

Traditional Irish music

[edit]Traditional Irish music sessions are held in several venues in the town.[40]

In the early 13th century, the poet and crusader Muireadhach Albanach Ó Dálaigh kept a school of poetry at Lissadell north of Sligo town. He was Ollamh Fileadh (High Poet) to the Ó Domhnaill kings of Tír Chonaill. The school appears to have been dissolved after the Norman invasion. In the 16th century, the poet Tadhg Dall Ó hÚigínn wrote many praise poems in strict Dán Díreach metre for local chiefs and patrons such as the O'Conor Sligo. He was killed for a satire he wrote on the O'Haras. The annals record the death in 1561 of Naisse mac Cithruadh, the "most eminent musician that was in Éireann", by drowning on Lough Gill.[citation needed]

In the 17th century, two brothers from County Sligo, Thomas and William Connellan from Cloonamahon, were among the last of the great Irish bards and harpists. Thomas is the author of the tune Molly MacAlpin, now known as Carolan's Dream, and William may have written Love is a Tormenting Pain and Killiecrankie.

Traditional musicians from Sligo active in the early 20th century include Michael Coleman, James Morrison and Paddy Killoran.[citation needed]

Festivals

[edit]Sligo hosts several festivals throughout the year, including Sligo Live, occurring every October; the Sligo Summer Festival, which celebrated the 400th anniversary of Sligo town; and the Fleadh Cheoil, which the town hosted in three consecutive years (1989, 1990 and 1991) and again in 2014 and 2015. Approximately 400,000 people attended the 2014 and 2015 festivals. During the festival, much of the music was played by musicians on the streets of Sligo.[citation needed]

The Sligo Jazz Project is held every July.[citation needed] Another annual festival, the Sligo Festival of Baroque Music, was started in 1995 and takes place on the last weekend of September.[41]

Theatre

[edit]Sligo also has a tradition of theatre, both professional and amateur. Sligo has had a theatre at least as far back as 1750, according to Wood-Martins’ History of Sligo, and often "her Majesty's servants from the Theatre Royal, Crow Street …. visited Sligo, even during the Dublin season, showing that in those days the townsfolk appreciated the Drama, for in some instances the company remained during several months".[citation needed]

There are now two full-time theatres in the town, including the Blue Raincoat Theatre Company, was founded in 1990 and based in Quay street.[42] Sligo is also home to Hawk's Well Theatre, a 340-seat theatre founded in 1982.[42]

In media

[edit]Sligo is the setting for author Declan Burke's series of hard boiled detective novels, featuring detective Harry Rigby.[43]

Sebastian Barry's novels The Secret Scripture and The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty are also set in Sligo town.

Sligo is the setting for John Michael McDonagh's 2014 darkly comedic drama film Calvary,[44] in which a priest continues to serve his parishioners despite their increased hostility towards him and the Catholic Church.

Together with Dublin, County Sligo is one of the two main settings for Sally Rooney's 2018 novel, Normal People. A 2020 adaptation made by BBC Three and Hulu was partially filmed in Sligo.[45]

Sport

[edit]Football

[edit]The town is home to 2012[update] League of Ireland Premier Division champions Sligo Rovers, who have played home matches at The Showgrounds since they were founded in 1928.

There are also a number of junior association football (soccer) clubs who play in the Sligo/Leitrim & District league from the town. These include Calry Bohemians, Cartron United, City United & St. John's FC who play in the Super League and Glenview Stars, MCR FC, Merville United & Swagman Wanderers who play in the Premier League.

Gaelic games

[edit]There are three GAA clubs located in and around the town, including Calry/St. Joseph's of Hazelwood, St John's of Cuilbeg and St Mary's of Ballydoogan with Coolera/Strandhill of Ransboro and Drumcliffe/Rosses Point GAA also being close by. Calry/St Joseph's and St Mary's compete in the Sligo Senior Football Championship while St John's compete in the Sligo Intermediate Football Championship. Calry/St Joseph's also compete in the Sligo Senior Hurling Championship. These clubs also field Junior, Ladies, Minor and Underage teams. Many of the major Gaelic football and hurling matches, such as the inter-county home games of Sligo or a club championship finals, take place at Markievicz Park.

Rugby

[edit]Sligo RFC is situated at Hamilton Park, Strandhill, 8 km west of the town. This club participates in the Ulster Bank All-Ireland League Division 2B.

Other sports

[edit]Sligo (in particular Strandhill) is a location for surfing, and there are several surf schools in the area.[citation needed]

There are two nearby golf courses, County Sligo (Rosses Point) Golf Club and Strandhill Golf Club. Also just north of the borough boundary at Lisnalurg, there is Pitch and Putt called Bertie's. Rosses Point hosted the West of Ireland Championship in which future golfing star Rory McIlroy won in consecutive years (2005 and 2006).

Two basketball clubs are based in the town. These are Sligo All-Stars (located at the Mercy College Gymnasium) and Sligo Giant Warriors (whose venue is the Sligo Grammar Gymnasium).

Sligo Racecourse at Cleveragh hosts race days at least 8 times per year.

Administration

[edit]Sligo was administered by its own local oireachtas and the kings of Cáirbre Drom Cliab until the English conquest in the early 17th century. This territory corresponds closely to the newly created Sligo Borough District.

Sligo town then became an incorporated municipal borough with a Royal charter issued by the British King James I between 1613 and 1614. Sligo has had a mayor since incorporation in 1613. It had the right to elect 12 burgesses to the corporation. It was one of ten boroughs retained under the Municipal Corporations (Ireland) Act 1840. Under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, the area became an urban district,[46] while retaining the style of a borough corporation.[47]

Sligo Borough Corporation became a borough council in 2002.[48] On 1 June 2014, the borough council was dissolved and administration of the town was amalgamated with the Sligo County Council.[49][50] It retains the right to be described as a borough.[51] The chair of the borough district uses the title of mayor, rather than Cathaoirleach.[52]

As of the 2019 Sligo County Council election, the borough district of Sligo contains the local electoral area of Sligo–Strandhill, electing 10 seats to the council.[53]

Law enforcement

[edit]

From its foundation in the 13th century, Sligo was administered under local Fénechus (Brehon law) until the establishment of English Common law in the early 17th century after the battle of Kinsale. Courts were held regularly throughout the tuath at various buildings and on hilltops reserved for the purpose. Law enforcement was a function of the nobility and freemen of the area as no police force existed. No records survive from these early courts, but a case is recorded of a Dublin merchant being reimbursed by the local courts after he was fraudulently sold an out of date poem in the 1540s.[54] Sligo then came under English martial law and eventually the common law as administered from Dublin and from which descends the present system.

The modern Sligo Courthouse was built in 1878. It hosts regular District and Circuit Court sittings throughout the year, and occasionally the High Court.

After 1922 the establishment of Garda Síochána.

Sligo-Leitrim divisional headquarters of the Garda Síochána is on Pearse Road in the town on the site of the old RIC barracks.

Health services

[edit]Sligo provides hospital services to much of the North Western region. The two main hospitals are Sligo University Hospital (formerly General and Regional) and St. John's Community Hospital. There is also a private hospital at Garden Hill.

Education

[edit]As of 2016, 14.2 per cent of adults were educated to at most primary level only; a further 45.1 per cent attained second level while 40.7 per cent were educated to third level.[33]

There are five secondary schools in Sligo. These are two all-girls schools (Mercy College and Ursuline College), one all-boys (Summerhill College) and two mixed (Sligo Grammar School and Ballinode Community College).[55]

Sligo has a campus of Atlantic Technological University (ATU) located in Ash Lane. The university was formed in 2022 through the merger of: the Institute of Technology, Sligo (ITS); Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology (GMIT) and Letterkenny Institute of Technology (LYIT).[56] It offers courses in the disciplines of business, engineering, humanities and science.

St. Angela's College (outside the town proper) is a campus of the Atlantic Technological University, and offers courses in nursing and health studies, home economics and education.

Transportation

[edit]

Road

[edit]The main roads to Sligo are the N4 to Dublin, the N17 to Galway, the N15 to Lifford, County Donegal; and the N16 to Blacklion, County Cavan. The section of the N4 road between Sligo and Collooney is a dual carriageway. The first phase of this road was completed in January 1998, bypassing the towns of Collooney and Ballysadare. An extension to this road was completed in September 2005, and is known as the Sligo Inner Relief Road.

O'Connell Street – the main street in the town – was pedestrianised on 15 August 2006. Plans for the proposed redevelopment and paving of this street were publicly unveiled on 23 July 2008 in The Sligo Champion. The newspaper later revealed that people were not in favour of the pedestrianisation of the street.[citation needed] The street was reopened to traffic in December 2009.

Sligo has a certain amount of cycleways in proximity to the town and various road traffic calming measures have been installed helping to improve safety for pedestrians and cyclists. The Urban Cycle Sligo initiative, for example, created six cycle routes.[57]

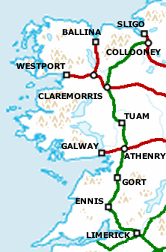

Rail

[edit]Sligo acquired a rail link to Dublin on 3 December 1862, with the opening of Sligo railway station.[58] Connections to Enniskillen and the north followed in 1881 and Limerick and the south in 1895. The line to Enniskillen closed in 1957 and passenger services to Galway-Ennis-Limerick closed in 1963. For many years Córas Iompair Éireann (CIÉ) kept the latter line open for freight traffic, before its full closure. The proposed Western Rail Corridor redevelopment project seeks to reopen it. In 1966 Sligo railway station was renamed Sligo Mac Diarmada Station after Irish rebel Seán Mac Diarmada from County Leitrim.[59] Irish Rail, the Republic of Ireland's state railway operator, runs inter-city rail services on the Dublin-Sligo railway line. There are currently[when?] up to eight trains daily each way between Sligo and Dublin Connolly, with a frequency of every two hours.[60]

Air

[edit]Sligo and County Sligo are served by Sligo Airport, 8 km (5.0 mi) from Sligo town and near Strandhill, though no scheduled flights operate out of the airport. The nearest airport with scheduled flights is Ireland West Airport near to Charlestown, County Mayo, 55 km (34 mi) away.

The Irish Coast Guard Helicopter Search & Rescue has been based at Sligo Airport since 2004, callsign Rescue 118. CHC Ireland provide 24 hour search and rescue using a Sikorsky S-92 helicopter.

The helicopter is operated by a crew of four, maintained and supported year round. The most northerly base in Ireland, it deals with the stern challenges posed by the Atlantic Ocean and the clifftop environment along the north-west coast.[61]

Bus

[edit]Bus Éireann operates four bus routes in the town: one serves the town centre and another the west of the town. The other two routes run from the town to Strandhill and Rosses Point respectively.[62] Bus Éireann also provides inter-city services to: Enniskillen, via Manorhamilton; to Derry; to Galway, via Ireland West Airport; and to Dublin, via Dublin Airport and towns along the N4 road.[63]

Bus Feda operates a route from Gweedore, County Donegal, via Sligo to Galway.[64]

Sligo Port

[edit]Sligo is one of just two operating ports on Ireland's northwest coast between Galway and Derry, the other being Killybegs. The harbour can accommodate ships with a maximum draft of 5.2 metres (17 ft) and a maximum length of 100 metres (330 ft); the Port of Sligo extends from the Timber Jetty for a distance of 1.3 kilometres (0.81 mi).

The Harbour Commissioners of Sligo administered the port from 1877 until Sligo County Council took over responsibility for the Harbour from Sligo Harbour Commissioners in June 2006.

Records show the development of Sligo's port, exporting agricultural goods to Britain and Europe, in the 13th century with the arrival of the Normans. In 1420 port dues were levied for the first time. Later, as a port under Gaelic lords the harbour continued to flourish. Control of the taxes or "cocket" of Sligo port became a sought after prize of local dynasties. Native merchant families, like the O'Creans wine importers being the most well known. Sligo traded with France, Spain and Portugal throughout the Middle Ages.

After incorporation into the British Empire from 1607 onward Sligo was an important port.[65][not specific enough to verify] During the 17th and 18th centuries, the port was used for the transit of significant quantities of cattle, hides, butter, barley, oats, and oatmeal being exported and with the city's linen exports well established. Imports included wood, iron, maize and coal. The town prospered due to the trade with wealthy merchants setting up homes along the then fashionable Castle Street and Radcliffe Street (later renamed Grattan Street).

During the time of the Great Famine 1847–1850, it is estimated that more than 30,000 people emigrated through Sligo Port, mainly to Canada and the United States.

The most notable ship companies to operate out of Sligo included Sligo Steam Navigation Company who introduced the first steamer in 1857, Messrs Middleton & Pollexfen, Harper Cambell Ltd and the former Sligo Harbour Commissioners who owned a number of dredgers used for maintenance of the Channel (McTernan, 1992).[66]

Linen was a major export also through Sligo port, with Pernmill road memorialising the linen textile mills.

When I was a child at Sligo I could see above my grandfather's trees a little column of smoke from "the pern mill," and was told that "pern" was another name for the spool, as I was accustomed to call it, on which thread was wound.

— W B Yeats

The Sligo docks played an important role in the history of the labour movement in Ireland. The 1913 Sligo Dock strike lasted for 56 days and was a precursor to the Dublin Lockout that occurred 6 months later. Unlike the Dublin Lockout, the Sligo Dock strike resulted in victory to the workers.

The port of Sligo declined during the 20th century with the decline of sail and steamships and the increasing size of cargo vessels.[67][better source needed] In modern times, the port handles cargoes of coal, timber, fish meal and scrap metal and around 25 ships per year dock in the harbour.[citation needed] In 2012 a feasibility study was undertaken into the dredging of the shipping channel.[citation needed]

Media

[edit]There are three local newspapers in Sligo: The Sligo Weekender – out every Thursday (formerly Tuesday); the free Northwest Express – out the first Thursday of each month; and The Sligo Champion – out every Tuesday (formerly Wednesday). Sligo Now is a monthly entertainment guide for the town, while Sligo Sport is a monthly sports-specific newspaper.[citation needed]

The town has two local/regional radio stations: Ocean FM, which broadcasts throughout County Sligo and parts of some bordering counties; and West youth radio station i102-104FM, which merged with its sister station i105-107FM in 2011 to create iRadio.[citation needed]

Notable people

[edit]Twinning

[edit]Sligo is twinned with the following places:

Everett, Washington, United States

Everett, Washington, United States Crozon, Brittany, France

Crozon, Brittany, France Illapel, Choapa Province, Chile

Illapel, Choapa Province, Chile Kempten, Bavaria, Germany

Kempten, Bavaria, Germany Tallahassee, Florida, United States[68]

Tallahassee, Florida, United States[68]

Gallery

[edit]-

Choir of Sligo Abbey

-

Interior of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception

-

Clock tower of the cathedral

-

Sligo Post Office in 1996

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The category other stated religions would include both Christian and non-Christian.

References

[edit]- ^ "Population Density and Area Size 2016". Census 2016. Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b "Census 2022 - F1015 Population". Central Statistics Office Census 2022 Reports. Central Statistics Office Ireland. August 2023. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ SCC. "ErrorFourZeroFour" (PDF). sligococo.ie. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Wood-Martin's History of Sligo, 1882

- ^

"History of Sligo". Sligo Borough Council – About Us. Archived from the original on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

The scallop shells [...] were once abundant in the estuary at the mouth of the Garavogue – a river once known as the 'Sligeach', or 'shelly place', giving Sligo its name

- ^ a b "Origins of Sligo/Slicech/Sligeach". Sligo Heritage. 10 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ Bergh, Stefan (1995). Landscape of the monuments. A study of the passage tombs in the Cúil Irra region, Co. Sligo, Ireland. Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetet Arkeologiska Undersökningar. ISBN 91-7192-945-2.

- ^ "Archaeology Ireland articles". Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ Danaher, Edward (2007). Monumental beginnings: the archaeology of the N4 Sligo Inner Relief Road. Wordwell Books. ISBN 978-1-905569-15-1.

- ^ Darcy, R.; Flynn, William (2008). "Ptolemy's map of Ireland: a modern decoding". Irish Geography. 41: 49–69. doi:10.1080/00750770801909375.

- ^ "Annals of the Four Masters". Celt.ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Wood-Martin, W.G. (1892). History of Sligo, County and Town. From the accession of James 1. to the Revolution of 1688. Vol. 2. Dublin: Hodge & Figgis.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Lady Erin statue". Sligo town website. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Charlotte-Blake-Thornley -Stoker-Bram-Abraham-Sligo-Dublin-ODonnells-Manus-the-Magnificent". bramstokerestate.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Norton, Desmond (2003). "Lord Palmerston and the Irish Famine Emigration: A Rejoinder". The Historical Journal. 46 (1): 155–165. doi:10.1017/S0018246X02002881. JSTOR 3133599. S2CID 162314147.

- ^ "More destruction on railways as Sligo train station set ablaze | Century Ireland". RTÉ.ie.

- ^ "County Profiles – Sligo". Western Development Commission. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ a b c "Topographical information. In Fióna Gallagher and Marie-Louise Legg, Irish Historic Towns Atlas, no. 24, Sligo" (PDF). Royal Irish Academy, Dublin. 2012. pp. 1–27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "1730 – St. Mary the Virgin & St. John the Baptist Cathedral, Sligo, Co. Sligo – Archiseek – Irish Architecture". Archiseek.com. 30 December 2009. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "2000 – Model Arts and Niland Gallery, Sligo, Co. Sligo – Archiseek – Irish Architecture". Archiseek.com. 31 December 2009. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ "Records of Protected Structures Proposed additions and deletions" (PDF). Sligo County Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ DellaSala, Dominick A. (2 May 2018). Temperate and Boreal Rainforests of the World: Ecology and Conservation. Island Press. ISBN 9781597266765. Retrieved 2 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Climate – Monthly Data – Markree". Met Éireann. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Sligo (Ireland) Agglomeration". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b c "Sapmap Area – Settlements – Sligo". Census 2016. CSO. 2016. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ "St. Anne's Church, Cranmore". St. Anne's Church, Cranmore. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "St. Joseph's and Calry". St. Joseph's and Calry parish. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ "Sligo-Leitrim Islamic Cultural Centre". Sligo-Leitrim Islamic Cultural Centre. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Sligo St. Thomas Indian Orthodox Church". Indian (Malankara) Orthodox Syrian Church. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2021/1130 of 5 July 2021 setting out the list of regions eligible for funding from the European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Fund Plus and of Member States eligible for funding from the Cohesion Fund for the period 2021-2027 (notified under document C(2021) 4894)

- ^ a b "Sligo". Western Development Commission. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to Sligo". Sligo Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Sligo's educated workforce and quality of life can make up for its remoteness". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 16 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Sligo Retail Park - Location". sligoretailpark.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Mystery donor gives valuable Yeats art to Sligo arts centre". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 27 January 2018. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Poetry readings launch Sligo's 60th Yeats Summer School". rte.ie. RTÉ News. 27 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Sligo council to erect plaque to honour Spike Milligan". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 9 November 2004. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Sligo Town". discoveringireland.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "About the Sligo Festival of Baroque Music". sligobaroquefestival.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

Sligo Festival of Baroque Music began life in 1995 as Sligo Early Music Festival

- ^ a b "Cultural Sligo". sligotourism. Sligo Tourism Ltd. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Celtic Crime: Declan Burke's Sligo". wordpress.com. 13 July 2010. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Calvary: Sundance 2014 – first look review". The Guardian. 20 January 2014. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Miner, Adele (27 August 2019). "Sarah Greene spills the beans on new series Normal People". VIP Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Clancy, John Joseph (1899). A handbook of local government in Ireland: containing an explanatory introduction to the Local Government (Ireland) Act, 1898: together with the text of the act, the orders in Council, and the rules made thereunder relating to county council, rural district council, and guardian's elections: with an index. Dublin: Sealy, Bryers and Walker. p. 426.

- ^ Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, s. 22: County districts and district councils (61 & 62 Vict., c. 37 of 1898, s. 22). Enacted on 12 August 1898. Act of the UK Parliament. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 3 November 2022.

- ^ Local Government Act 2001, 6th Sch.: Local Government Areas (Towns) (No. 37 of 2001, 6th Sch.). Enacted on 21 July 2001. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 3 August 2022.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 24: Dissolution of town councils and transfer date (No. 1 of 2014, s. 24). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 21 May 2022.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014 (Commencement of Certain Provisions) (No. 3) Order 2014 (S.I. No. 214 of 2014). Signed on 22 May 2014 by Phil Hogan, Minister for the Environment, Community and Local Government. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 3 November 2022.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 19: Municipal districts (No. 1 of 2014, s. 19). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 5 September 2020.

- ^ Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 37: Alternative titles to Cathaoirleach and Leas-Chathaoirleach, etc. (No. 1 of 2014, s. 37). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 3 November 2022.

- ^ County of Sligo Local Electoral Areas and Municipal Districts Order 2018 (S.I. No. 632 of 2018). Signed on 19 December 2018. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 31 October 2022.

- ^ O'Dowd, Mary (2 May 1991). Power, Politics, and Land: Early Modern Sligo, 1568–1688. Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University of Belfast. ISBN 9780853894049. Retrieved 2 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Sligo Find secondary schools". School Days. Archived from the original on 17 August 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Atlantic Technological University: Name of State's newest university revealed". The Irish Times. Dublin. 23 November 2021. ISSN 0791-5144. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ "All Routes". Urban Cycle Sligo. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Butt, R.V.J. (1995). The Directory of Railway Stations. Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 213. ISBN 1-85260-508-1.

- ^ Gilligan, James (19 December 2006). "Restore name to Sligo rail station". Sligo Weekender. Sligo Weekender Ltd. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- ^ "Timetables and Service Updates – Iarnród Éireann – Irish Rail". Archived from the original on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ Irish Coast Guard – Search & Rescue Archived 6 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sligo City Services – Bus Éireann". Bus Éireann timetable. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ "Intercity Services – Bus Éireann". Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ McDonagh, Marese (25 January 2017). "Bus Feda owner rejects Bus Éireann's accusations". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Sligo County Council, 2008

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Search Results – sligo quays". catalogue.nli.ie. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "Tallahassee Irish Society". Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.