Mandarin square

| Mandarin square | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

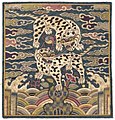

Qing dynasty mandarin square, 6th civil rank, about 30 cm square. | |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 補子 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 补子 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Master's patch | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Bổ tử | ||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 補子 | ||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 흉배 | ||||||||

| Hanja | 胸背 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||

| Manchu script | ᠰᠠᠪᡳᡵᡤᡳ | ||||||||

| Möllendorff | sabirgi | ||||||||

| English name | |||||||||

| English | Mandarin square/ rank badge | ||||||||

A mandarin square (Chinese: 補子), also known as a rank badge, was a large embroidered badge sewn onto the surcoat of officials in Imperial China (decorating hanfu and qizhuang), Korea (decorating the gwanbok of the Joseon dynasty), in Vietnam, and the Ryukyu Kingdom. It was embroidered with detailed, colourful animal or bird insignia indicating the rank of the official wearing it. Despite its name, the mandarin square (buzi) falls into two categories: round buzi and square buzi.[1]: 396 Clothing decorated with buzi is known as bufu (simplified Chinese: 补服; traditional Chinese: 補服) in China.[2] In the 21st century, the use of buzi on hanfu was revived following the Hanfu movement.

China

[edit]The history of the square-shaped buzi is unclear. However, in the Yuan dynasty encyclopaedia Shilin Guangji (事林廣記), as well as contemporary Persian paintings of the Mongol court, there are pictures showing officials wearing clothing with squares on the back, decorated with flora, animals and birds.[3] By the Yuan dynasty, the square-shaped buzi was already worn as clothing ornaments.[4]: 235

Ming dynasty

[edit]

Mandarin squares were first authorized for the wear of officials in the sumptuary laws of 1391 of the Ming dynasty.[4]: 235 The use of squares depicting birds for civil officials and animals for military officials was an outgrowth of the use of similar squares, apparently for decorative use, in the Yuan dynasty.[5] The original court dress regulations of the Ming dynasty were published in 1368, but did not refer to badges as rank insignia.[6] These badges continued to be used through the remainder of the Ming and the subsequent Qing dynasty until the imperial system fell in 1912.

Ming nobles and officials wore their rank badges on full-cut red robes with the design stretching from side to side, completely covering the chest and back. This caused the badges to be slightly trapezoidal with the tops narrower than the bottom.[7] The Ming statutes never refer to the number of birds or animals that should appear on the badges. In the beginning, two or three were used. In a typical example of paired birds, they were shown in flight on a background of bright cloud streamers on a gold background. Others showed one bird on the ground with the second in flight. The addition of flowers produced an idealized naturalism.[8][9]

Qing dynasty

[edit]

There was a sharp difference between the Ming and Qing styles of badges: the Qing badges were smaller with a decorative border.[10] And, while the specific birds and animals did not change much throughout their use, the design of the squares underwent an almost continual evolution.[11] According to rank, Qing-dynasty nobles had their respective official clothes. Princes, including Qin Wang and Jun Wang, usually wore black robes as opposed to the blue robes in court, and had four circular designs, one on each shoulder, front, and back, as opposed to the usual front-and-back design. Specifically, princes of the blood used four front-facing dragons, Qin Wang had two front-facing and two side-facing dragons, and Jun Wang had four side-facing ones; all had five claws on each foot. Beile and Beizi had a circular design on their official clothing, the former having two front-facing dragons, the latter two side-facing ones; these dragons had only four claws on each foot, and are referred to as "drakes" or "great serpents" (巨蟒 jù-mǎng). National duke, general, efu, "commoner" duke, marquis and count had two front-facing, four-clawed dragons on square designs, whereas viscount and baron had cranes and golden pheasants, as for mandarins of the first and second class.

-

3rd civil rank (peacock). Mid 19th century. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

-

2nd military rank (lion). Late 18th cent. Art Gallery of New South Wales

-

3rd military rank (leopard). 19th or early 20th century. Chester Beatty Library

-

Members of three generations of a lineage are shown in Qing mandarin attire, complete with mandarin squares

Comparative table across dynasties

[edit]

The specific birds and animals used to represent rank varied only slightly from the inception of mandarin squares until the end of the Qing dynasty. Officials who held a lower position or did odd jobs used the magpie during the Ming dynasty. Supervising officials used xiezhi. Musicians used the oriole. The following tables[12] show this evolution:

Military

[edit]| Rank | Ming (1391–1526) | Ming and Qing (1527–1662) | Late Qing (1662–1911) | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lion | Lion | Qilin (after 1662) |

|

| 2 | Lion | Lion | Lion | |

| 3 | Tiger or leopard | Tiger | Leopard (after 1664) | |

| 4 | Tiger or leopard | Leopard | Tiger (after 1664) | |

| 5 | Bear | Bear | Bear | |

| 6 | Panther | Panther | Panther | |

| 7 | Panther | Panther | Rhinoceros (after 1759)[13] | |

| 8 | Rhinoceros | Rhinoceros | Rhinoceros | |

| 9 | Rhinoceros | Sea horse[14] | Sea horse[15] |

Civil

[edit]| Rank | Ming (1391–1526) | Ming and Qing (1527–1662) | Late Qing (1662–1911) | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Crane or golden pheasant | Crane | Crane |

|

| 2 | Crane or golden pheasant | Golden pheasant | Golden pheasant |

|

| 3 | Peacock or wild goose | Peacock | Peacock |

|

| 4 | Peacock or wild goose | Wild goose | Wild goose |

|

| 5 | Silver pheasant | Silver pheasant | Silver pheasant |

|

| 6 | Egret or mandarin duck | Egret | Egret |

|

| 7 | Egret or mandarin duck | Mandarin duck | Mandarin duck[16] |

|

| 8 | Oriole, quail or paradise flycatcher | Oriole | Quail |

|

| 9 | Oriole, quail or paradise flycatcher | Quail | Paradise flycatcher[17] |

21st century

[edit]The use of the round-shaped and square-shaped buzi has been revived in China following the Hanfu movement.

Korea

[edit]Korean rank badge (흉배 in Korean) is a small panel of embroidery that would have served to indicate the status of a government official in the Choson dynasty Korea (1392–1910). Made in the nineteenth century, it shows a pair of black and white leopards, one above the other in opposing stance, surrounded by stylised cloud patterns in pink, purple and pale green upon a blue background. It would have been worn by a military official from the first to third ranks. Leopards and tigers, respected for their strength and courage in Korea, were used for the dress of military officials while civil officials wore crane motifs. This badge shows the distinctively spotted animals among rocks, waves and clouds in a pattern which remained virtually unchanged for 300 years.

-

Korean rank badge, 1850-1900, Victoria & Albert Museum (no. FE.272-1995)

Vietnam

[edit]-

Annamite (Vietnamese) badge, Nguyễn dynasty (19th century), civilian 8th rank.

-

Mandarins of the Nguyen dynasty (circa 1820). The Mandarin on the left is a "man of letters", with a stork on his chest and the one on the right is a military Mandarin, signified by a boar.[18]

See also

[edit]- Tablion

- Chinese hat knob

- Hanfu, Gwanbok, Qizhuang

- Nine-rank system, for an earlier system for ranking officials in China

- Chinese auspicious ornaments in textile and clothing

References

[edit]- ^ A history of Chinese science and technology. Volume 2. Yongxiang Lu, Chuijun Qian, Hui He. Heidelberg. 2014. ISBN 978-3-662-44166-4. OCLC 893557979.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Guide to Hanfu Types Summary & Dress Codes (Ming Dynasty)". www.newhanfu.com. 4 April 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Cammann, Schuyler (1944). "University College London". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 8 (2): 71–130. doi:10.2307/2717953. JSTOR 2717953.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Michael (1999). The arts of China (4th expanded and rev ed.). Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21876-0. OCLC 40200406.

- ^ Cammann, Schuyler: "Birds and Animals as Ming and Ch'ing Badges of Rank", Arts of Asia (May to June 1991), page 89.

- ^ Schuyler Cammann (August 1944). "The Development of the Mandarin Square". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 8 (2): 75–76. doi:10.2307/2717953. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 2717953. Wikidata Q117360120.

- ^ Cammann, Schuyler: "Chinese Mandarin Squares, Brief Catalogue of the Letcher Collection", University Museum Bulletin Vol 17, No 3 (June 1953), pages 8–9.

- ^ Cammann, Schuyler: "Chinese Mandarin Squares, Brief Catalogue of the Letcher Collection", University Museum Bulletin Vol 17, No 3 (June 1953), page 9.

- ^ Schuyler Cammann (August 1944). "The Development of the Mandarin Square". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 8 (2): 95. doi:10.2307/2717953. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 2717953. Wikidata Q117360120.

- ^ Cammann, Schuyler, "Birds and Animals as Ming and Ch’ing Badges of Rank", Arts of Asia (May–June 1991), page 90.

- ^ Jackson, Beverley & Hugus, David, Ladder to the Clouds, Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 1999, Chapter 15, pages 215–289.

- ^ Katarzyna Zapolska (2014). "Mandarin squares as a form of rank badge and decoration of Chinese robes". Art of the Orient. 3: 53–70. ISSN 2299-811X. Wikidata Q117360068.

- ^ Note that the rhinoceros is depicted as a buffalo, rather than as a rhinoceros.

- ^ Note that the sea horse is depicted as a horse living under water, rather than as a seahorse.

- ^ Jackson, Beverley & Hugus, David, Ladder to the Clouds, Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 1999, Table 4, page 133;

- ^ Marcin Latka. "Portrait of a young official". artinpl. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Jackson, Beverley & Hugus, David, Ladder to the clouds, Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 1999, Table 3, page 133.

- ^ Crawfurd, John (1828). Journal of an embassy from the Governor-General of India to the courts of Siam and Cochin-China : exhibiting a view of the actual state of those kingdoms. London: H. Colburn. pp. 262–263.

Further reading

[edit]- "Rank insignia for military officers of the imperial court", in: Welch, Patricia Bjaaland (2008), Chinese Art, Tuttle, pp. 110–111, ISBN 978-0-8048-3864-1

- Rank and Style: Power Dressing in Imperial China, Pacific Asia Museum, 2008, archived from the original on 7 October 2016, retrieved 19 June 2016

External links

[edit] Media related to Mandarin square at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mandarin square at Wikimedia Commons

![Mandarins of the Nguyen dynasty (circa 1820). The Mandarin on the left is a "man of letters", with a stork on his chest and the one on the right is a military Mandarin, signified by a boar.[18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d4/Quan_phuc_nha_Nguyen.gif/120px-Quan_phuc_nha_Nguyen.gif)