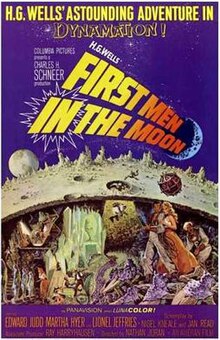

First Men in the Moon (1964 film)

| The First Men in the Moon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Nathan Juran |

| Screenplay by | Nigel Kneale Jan Read |

| Based on | The First Men in the Moon 1901 (novel) by H. G. Wells |

| Produced by | Charles H. Schneer |

| Starring | Edward Judd Martha Hyer Lionel Jeffries |

| Cinematography | Wilkie Cooper |

| Edited by | Maurice Rootes |

| Music by | Laurie Johnson |

| Color process | Technicolor |

Production company | Ameran Films |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 103 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1,650,000 (US/Canada)[2] |

First Men in the Moon (also known H.G. Wells' First Men in the Moon) is a 1964 British science fiction film, produced by Charles H. Schneer, directed by Nathan Juran, and starring Edward Judd, Martha Hyer and Lionel Jeffries.[3] The film, distributed by Columbia Pictures, is an adaptation by screenwriter Nigel Kneale of H. G. Wells' 1901 novel The First Men in the Moon.

Ray Harryhausen provided the stop-motion animation effects, which include the Selenites, giant caterpillar-like "Moon Cows" and the large-brained Grand Lunar.[4][5]

Plot

[edit]In 1964, the United Nations has launched a rocket flight to the Moon. A multi-national group of astronauts in the UN spacecraft land, believing themselves to be the first lunar explorers. However, upon embarking on their debut moonwalk, they discover a battered Union Jack flag on the surface and a handwritten note, dated some 65 years earlier, claiming the moon on behalf of Queen Victoria. Stranger still, the note is written on the back of a court summons for one Katherine Callender from the village of Dymchurch in England.

Attempting to trace Callender in the records office in Dymchurch in Kent, south-east England, the UN authorities discover that she has died, but that her widowed husband Arnold Bedford is still living in a nursing home known as "The Limes". The home's staff do not let him watch television reports of the Moon expedition because, according to the matron, it "excites him". Bedford's repeated lunar claims are dismissed as senile delusion. The UN representatives question him about the Moon, and he tells them his story, which is shown in flashback.

In 1899, Arnold Bedford lives in a romantic spot, Cherry Cottage, next to a canal lock in Dymchurch. His fiancée, Katherine Callender, known as Kate, arrives by car (driving herself), visiting the house for the first time. It is implied that Bedford is in financial difficulties by a letter about his rent being well past due. They meet a nearby neighbour, inventor Joseph Cavor, who wants to buy the cottage, just in case his experiments should damage it. Kate agrees to this on Bedfords behalf. Bedford begins spending time at Cavor's house, where the inventor has a large laboratory. He has developed a substance, Cavorite, that will let anything it is applied to or made of nullify the force of gravity. He plans to use it to travel to the Moon. Bedford has deeds drawn up and signed in Kate's name selling the cottage to Cavor for £5000...(in reality he is selling something that he does not own).

Cavor tempts Bedford by telling him there are gold nuggets on the Moon. He has already built a spherical spaceship in the greenhouse next to the cottage. The sphere is lined inside with green velvet, and it has electric lights. There is an explosion at Cavor's house just as Kate arrives at the cottage. This is caused by Cavor's assistant, Gibbs, leaving for the local pub instead of watching the boiler used for processing the Cavorite. He shows her deep sea diving suits intended to keep them both alive while on the lunar surface. The production of Cavorite is increased. Kate brings some things for the trip: gin and bitters, chickens, and an elephant gun. But she gives Bedford an ultimatum: "Cavorite or me". Back at the cottage, Kate is served with a summons by a bailiff accompanied by a silent policeman. She has been charged with selling a property she does not own. Bedford and Cavor are just about to leave when Kate angrily hammers on the outside of the sphere wanting to know what he has done. They pull her inside just before the sphere launches.

On the long journey to the Moon they eat only sardines. The principle of steering is by rolling up blinds covering sections of the sphere to lessen the effect of the Cavorite in that one area and thus propelling it in that direction, but opening a blind causes the sphere to veer toward the Sun. They eventually crash land on the lunar surface, and both men don the diving suits. Kate is placed inside an air-tight compartment since she is unable to accompany them.

While exploring the lunar surface, Bedford and Cavor fall down a vertical shaft, where there is breathable air. They discover an insectoid population, the Selenites, living beneath the surface in large caverns. (Cavor coins this name for the creatures after the Greek goddess of the Moon, Selene). While being herded by them, Bedford attacks a group of Selenites out of fear, killing several, despite Cavor's horrified protests. After escaping, the two men discover that the sphere, still containing Kate, has been dragged into the underground city.

They are attacked by a giant caterpillar-like "Moon Bull", which pursues them until the Selenites are able to dispatch it with their ray weapons. Cavor and Bedford see the city's power station, a perpetual motion machine powered by sunlight. The Selenites quickly learn English and interrogate Cavor, who believes they wish to exchange scientific knowledge. Cavor has a discussion with the "Grand Lunar", the ruling entity of the Selenites. Bedford makes the assumption that Cavor, and presumably all humanity, is now on trial, he attempts to kill the Grand Lunar with the elephant gun, failing because of Cavor's interference. Now running for their lives, Bedford manages to find the sphere, and he and Kate are able to make an escape. Cavor voluntarily stays behind on the Moon.

Bedford flies the sphere up a vertical shaft of light, shattering the massive window-like covering at the top, and he and Kate return to Earth. He concludes his story by mentioning that they came down in the sea off the coast of Zanzibar, their sphere sinking without trace. They managed to swim ashore, but Cavor's ultimate fate remained unknown to them.

In the present, Bedford, the UN party, and newspaper reporters watch on television the latest events on the Moon. The UN astronauts have broken into the Selenite's underground city and find it deserted and decaying. The ruined city begins to crumble and collapse, forcing the astronauts to hastily retreat to the surface. Seconds later the entire lunar city is completely destroyed. Bedford realizes that the Selenites must have succumbed to Cavor's common cold virus to which they had no immunity.

Cast

[edit]

- Edward Judd as Arnold Bedford

- Martha Hyer as Kate Callender

- Lionel Jeffries as Joseph Cavor

- Miles Malleson as Dymchurch registrar

- Norman Bird as Stuart

- Gladys Henson as nursing home matron

- Hugh McDermott as Richard Challis, UN Space Agency

- Betty McDowall as Margaret Hoy, UN Space Agency

- Huw Thomas* as the first news announcer

- Valentine Dyall* as the second news announcer

- Erik Chitty* as Gibbs, Cavor's servant in Dymchurch

- Peter Finch* as the bailiff

- Marne Maitland* as Dr. Tok, UN Space Agency

* Not credited on-screen.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Harryhausen was planning on following Jason and the Argonauts (1963) with a version of H.G. Wells' 1904 novel The Food of the Gods and How It Came to Earth when he met with writer Nigel Kneale. Harryhausen had long wanted to film Wells' First Men in the Moon but producer Charles Schneer was not enthusiastic, in part due to worries about the film's period setting. Ray remembered "Charles would look at me and bring up the same logical arguments, namely that there was no variety in it, and that space exploration had advanced to such a degree that it would seem difficult to make the story seem believable to modern audiences".[6] Kneale thought it was an excellent idea. Being also a fan of the novel, he came up with a brilliant concept: a prologue and epilogue structure that would frame the story. By using this argument, Nigel Kneale and Ray Harryhausen managed to persuade Schneer to make it[7] as it solved the problem of Schneer's misgivings by bringing the storyline up to date, while still preserving the essence of Wells' story.[8]

Schneer said Kneale "is a very dour, straightforward, serious classicist. He was recognized in England as being the contemporary science-fiction screenwriter. I hired him because we needed his technical expertise. Then, we superimposed on that what we thought audiences would appreciate".[9]

Another writer was brought on to rework Kneale's script. According to Kneale: "They wanted to jazz it up, make it funnier than I had imagined". He says this inspired the casting of Lionel Jeffries.[10]

Kneale said in the book, Judd's character "was a blundering creature and it seemed important to keep that".[11] The writer says he knew that a country would get to the Moon relatively soon and discover there were no Selenites. This is why he added to the script that the Selenites were wiped out by a cold virus carried to the Moon by the professor, an idea Kneale says he took directly from The War of the Worlds.[11]

Director

[edit]This was the third collaboration between producer Charles Schneer and director Nathan Juran.[4] Schneer said Juran "was an excellent man for what he did, but he wasn't an actor's director. Many of our actors were used to more help from a director than he gave them. They felt a little adrift when they were expected to get on with their work without any great directorial assist. Jerry wasn't very patient with actors. He couldn't tolerate actors who wanted to know what their character's motivation was. He wanted to get on with the job he was hired to do".[9]

Casting

[edit]Schneer cast Judd from his performance in The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961).[9] Edward Judd was under contract to Columbia Pictures. "I had never done anything like that at the time, so I thought it would be fun", Judd said. "Since Lionel was already a great chum of mine, I knew we would have laughs on the set".[12]

Martha Hyer's character was not in the original drafts of the scripts but was introduced later.[13]

Some of the Selenite characters were played by children.[14]

Designs

[edit]

Ray Harryhausen used NASA blueprints as inspiration for the UN's lunar lander when he was designing the film's sets.[4]

Sculptor Bryan Kneale constructed the Selenites from Harryhausen's designs.

Spacesuits used

[edit]The spacesuit type worn by the film's UN Astronauts is actually the Windak high-altitude pressure suit,[15] developed for the Royal Air Force. Each was fitted with a 1960s-type aqualung cylinder worn as a backpack. These pressure suits would also be used in two Doctor Who stories: William Hartnell's final story "The Tenth Planet" (1966) and the Patrick Troughton-era "The Wheel in Space" (1968). They also appear in the original Star Wars trilogy as the costumes for Bossk and Bo Shek. [citation needed]

Shooting

[edit]Filming began on 1 October 1963.[16]

Schneer convinced Harryhausen the film's commercial prospects would be improved if it was shot in Panavision. "Ray was terrified of Panavision", said the producer. "All I had to do was suggest something different to him, and he would get nervous".[9]

"After you got past the first couple of reels, it was a funny film", said Juran. "Lionel was a swell actor. I liked him very much. His performance added immeasurably to the picture's entertainment value. He played it tongue-in-cheek but being such a good comic actor he controlled himself and never went too far. He made a great team with Edward Judd. Their personalities, one against the other, were just perfect".[4]

"It was fun to do, but it was bloody hard work," said Judd. "Lionel called it 'acting with chalk marks' because we were pointing at things that weren't there and dealing with blue backing and traveling mattes".[12]

Harryhausen would explain to the actors what the creatures would eventually look like just before they shot the scenes involving them.[12] He was effusive about Jeffries saying, "Lionel is one of those rare breed of actors who is not only accomplished in his field but also enjoys what he is doing and has the added bonus of having an imagination. I would show him drawings of the effects scenes and he would know instantly what was required and how it would look, even offering suggestions".[17]

"Lionel and I didn't like Jerry's working methods too much," said Judd. "He was more of a technician than an actor's director. We always thought of him as an art director, which of course he had been".[12]

In the scene where Kate is X-rayed by the Selenites, the stop-motion skeleton seen was one that previously appeared in the 1963 movie Jason and the Argonauts.[18]

Reception

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]Among contemporary reviews, Variety wrote, "Ray Harryhausen and his special effects men have another high old time in this piece of science-fiction hokum filmed in Dynamation", adding that "Wells' novel and has been neatly updated", and concluding that "The three principals play second fiddle to the special effects and art work, which are impressive in color, construction and animation".[19]

However, The New York Times wrote, "Only the most indulgent youngsters should derive much stimulation - let alone fun - from the tedious, heavyhanded science-fiction vehicle that arrived yesterday from England".[20]

The Guardian called it "good of its type".[21]

TV Guide called it "An enjoyable science fiction film".[22] and Blu-ray.com highly recommended the film as "a fun and exciting viewing experience".[23]

Box-office

[edit]Kinematograph Weekly called the film a "money maker" at the British box office for 1964.[24]

Nonetheless the film was a box-office disappointment. Harryhausen felt this was due to the inclusion of too much comedy.[13]

Schneer said he preferred the film to Jason and the Argonauts because "it was set in the Victorian era, whereas Jason took place in a much further removed period of history. Also, I thought the humor in it was delicious, whereas there wasn't much humor in Jason." The producer says Harryhausen felt "fantasy film fans are dead serious about these pictures and have no sense of humor. So, who am I to quarrel with him?"[9]

Kneale says the final film was "...all right. It could have been better if it had been a bit less farcical; that would have been more imaginative."[11]

Legacy

[edit]Schneer says that when the real Moon landing happened, NASA "had no footage showing the space capsule separating from the 'mother ship' and landing on the Moon's surface. All they had were shots of Neil Armstrong walking around". NASA went to Columbia Pictures and used the opening sequence of First Men in the Moon for illustration purposes during the 1969 moon landing. "They used those portions of it which were applicable to their needs," said the producer.[9] This was a returned favor as five years before the real-life event, NASA had given Ray Harryhausen access to its blueprints for reference.[17]

Following the film, Harryhausen and Schneer did not work together for five years.[9]

Comic book adaptation

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Image (3)". Photobucket.

- ^ "Big Rental Pictures of 1964", Variety, 6 January 1965 p 39. Please note this figure is rentals accruing to distributors not total gross.

- ^ "First Men in the Moon". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Swires, Steve (May 1989). "Nathan Juran: The Fantasy Voyages of Jerry the Giant Killer Part Two". Starlog Magazine. No. 142. p. 58.

- ^ FIRST MEN IN THE MOON Monthly Film Bulletin; London Vol. 31, Iss. 360, (Jan 1, 1964): 134.

- ^ Yours Retro magazine; Issue 75; June 2024; p.37

- ^ Kinnard p. 49

- ^ Yours Retro magazine; Issue 75; June 2024; p. 37

- ^ a b c d e f g Swirde, Steve (February 1990). "Maestro of the Magic Tricks: Part Two of Interview with Charles Schneer". Starlog. p. 70.

- ^ Warren p. 56

- ^ a b c Warren p 62

- ^ a b c d Swires, Steve. "First Man on the Moon". Starlog. No. 160. p. 18.

- ^ a b Kinnard p 54

- ^ Yours Retro magazine; Issue 75; June 2024; p. 37

- ^ "Say; Hello Spaceman".

- ^ 'TOM JONES' FILM OPENS HERE OCT. 7: British Adaptation of Novel Stars Albert Finney Johnston Award Established Miss Hyer Plans 'Moon Trip' 3 Return to Movies 'The Suitor' Opens Today New York Times 17 Sep 1963: 31.

- ^ a b Yours Retro magazine; Issue 75; June 2024; p. 38

- ^ Yours Retro magazine; Issue No. 75; June 2024; p. 37

- ^ "First Men in the Moon". Variety. 1 January 1964.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (26 November 1964). "The Screen: Moondust; New Space Trip Film Opens at the Capitol". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Cynical, but impressive". The Guardian. 21 September 1964: 4.

- ^ "First Men In The Moon". TVGuide.com.

- ^ "First Men in the Moon Blu-ray".

- ^ Altria, Bill (17 December 1964). "British Films Romp Home - Fill First Five Places". Kinematograph Weekly. p. 9.

- ^ "Gold Key: First Men in the Moon". Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Gold Key: First Men in the Moon at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

Bibliography

[edit]- Kinnard, Roy (September 1979). "First Men on the Moon". Fantastic Films. pp. 48–54.

- Newsom, Ted (Spring 1995). "Dynamation Ray Harryhausen Part Two". Imagi Movies. Vol. 2, no. 3. pp. 14–28.

- Walker, Kenneth (August 1980). "The A to Z of Creating First Men in the Moon". Starlog. pp. 38–41.

- Warren, Bill (March 1989). "Nigel Kneale Part Two". Starlog. pp. 52–56, 62.

External links

[edit]- 1964 films

- 1960s science fiction films

- 1960s science fiction adventure films

- British space adventure films

- British science fiction films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Films about astronauts

- Films based on works by H. G. Wells

- Films set in 1899

- Films set in 1964

- Films set in England

- Films set in outer space

- Films set on the Moon

- Films shot in England

- British monster movies

- 1960s monster movies

- Films using stop-motion animation

- Films directed by Nathan Juran

- Films adapted into comics

- Films scored by Laurie Johnson

- Films produced by Charles H. Schneer

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s British films

- English-language science fiction horror films

- English-language science fiction adventure films